Who Had the Better Camera?

"These two St. Vital boys": Photo as found in

The Winnipeg Tribune, Uni. of Manitoba

Readers may know that I have been searching through digitized issues of The Winnipeg Tribune, a once-fine Canadian newspaper, for material related to the approx. 1,000 Canadians who served in Combined Operations - and were therefore "on loan to the British Navy" as mentioned above in the photo's caption.

I would say that a good supply of information about the Navy boys who manned landing crafts at many significant raids and invasions, from Dieppe to Normandy, can be found in The Trib. I have offered many articles on this site and they are available to readers by way of the 'click on HEADINGS' in the right margin. Go to 'articles re Combined Operations.'

I would say that a good supply of information about the Navy boys who manned landing crafts at many significant raids and invasions, from Dieppe to Normandy, can be found in The Trib. I have offered many articles on this site and they are available to readers by way of the 'click on HEADINGS' in the right margin. Go to 'articles re Combined Operations.'

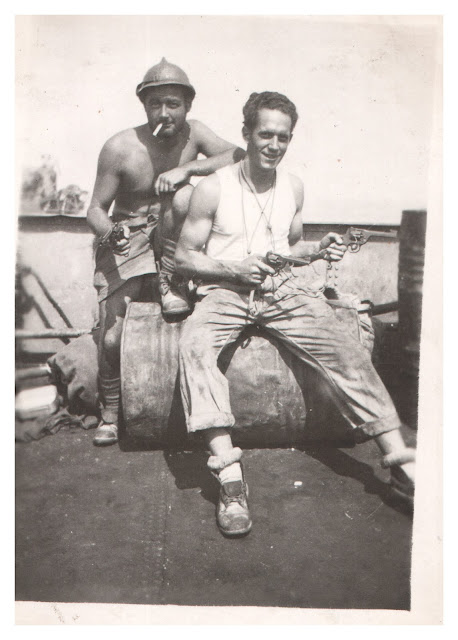

Recently, the above somewhat grainy photograph of two Canadian boys "In Sicily" caught my eye in the October 9, 1943 issue. I recognized one of the two St. Vital boys mentioned in the caption. Not by the likeness to another photo, but by the name, i.e., Jack Trevor.

Jack's name is attached to one other photograph I possess, part of a fine collection sent to me by Gary Spencer, the son of Joe Spencer (RCNVR, Combined Operations), a veteran of Dieppe and the invasions of North Africa, Sicily and Italy.

Caption: Jack Trevor, Sicily. circa 1943

Photo Credit - Joe Spencer

I thought readers might like to see Mr. Spencer's fine photograph. I don't know what kind of camera he used but the quality really outshines the one found in the newspaper. That being said, I'm very happy to have both. With details found in the news caption, I've been able to have some fun.

Thanks to Google Maps I also discovered that close to Jack's former home address (i.e., 34 Hull Avenue) stands the St. Vital Museum, and they regularly distribute a history-filled newsletter. So... I sent along the two photos and the following (in part):

Jack was a volunteer in the Royal Canadian Navy Volunteer Reserve, and sometime before the invasion of Sicily (July 10, 1943; 75 years ago) he also volunteered for the Combined Operations organization and was therefore "on loan to the British Navy" as stated.

My father was the same, from 1941 - 45, and they may have crossed paths while transporting troops and all materials of war on landing crafts in Sicily and/or during the invasion of Italy (beginning Sept. 3, 1943).

In the second photo, Jack is likely onboard a landing craft, mechanised (LCM) or landing craft, tank (LCT), perhaps in the Strait of Messina between Sicily and Italy.

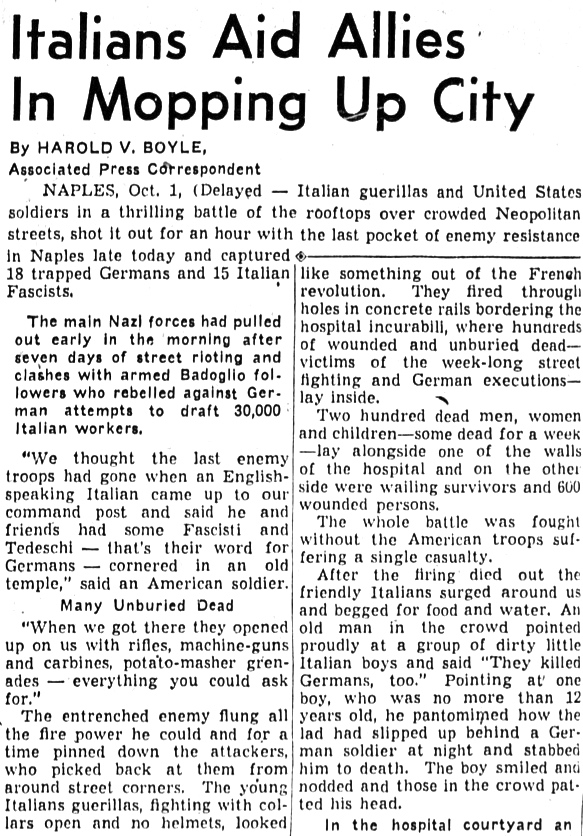

I went on to say that I would send the St. Vital Museum a story that might explain where Jack obtained the two revolvers he is carrying.

That story can be found here: Articles: Italy, Oct.2 - 6, 1943 - Pt 11.

Please link to more entries related to research at Article: Canadian War Correspondents on the Move

Unattributed Photos GH

Jack was a volunteer in the Royal Canadian Navy Volunteer Reserve, and sometime before the invasion of Sicily (July 10, 1943; 75 years ago) he also volunteered for the Combined Operations organization and was therefore "on loan to the British Navy" as stated.

My father was the same, from 1941 - 45, and they may have crossed paths while transporting troops and all materials of war on landing crafts in Sicily and/or during the invasion of Italy (beginning Sept. 3, 1943).

In the second photo, Jack is likely onboard a landing craft, mechanised (LCM) or landing craft, tank (LCT), perhaps in the Strait of Messina between Sicily and Italy.

I went on to say that I would send the St. Vital Museum a story that might explain where Jack obtained the two revolvers he is carrying.

That story can be found here: Articles: Italy, Oct.2 - 6, 1943 - Pt 11.

Please link to more entries related to research at Article: Canadian War Correspondents on the Move

Unattributed Photos GH