That First Christmas in Germany

A. Robert Prouse, in the book

"Ticket to Hell via Dieppe", writes about his experiences as a prisoner of war in Germany after his capture on the beaches of Dieppe, France. His memoirs are honest and enlightening, and I share below a few excerpts in order to provide a glimpse of what life was sometimes like inside a prison camp, in this case Stalag IXC on the outskirts of Molsdorf.

We Were Not Completely Forgotten

That first Christmas in Germany was a lonely one.

It started me thinking too much of loved ones and home.

I began to formulate thoughts of escape.

We received Christmas crackers from an organization

in England and were extremely surprised when

'popping' them to find map sections falling out.

Each map section showed various parts of Germany plus

adjoining countries, such as Belgium, Holland and France.

They were on very thin rice paper and were

an invaluable asset for would-be escapees.

We silently thanked the powers who had devised

this method of delivery, at the same time wondering

how it had been missed by German Intelligence.

The maps gave us all feelings of hope and elation

(the same feelings we got when hearing some 'good' propaganda,

even though it often turned out to be false), and helped overcome

some of the recurring feelings of depression, loneliness, anxiety

and fear of what the future held. It gave us a lift to know

that we were not 'lost' and completely forgotten.

Page 41

* * * * *

When the Parcels Arrived, It was Heaven

After our act of defiance, the camp settled down

to a normal routine. We were up each day at 6:00 a.m.,

and until 'lights out' at 10:00 p.m. the day was organized

around a boring schedule punctuated by mealtimes

and welcome cigarette breaks.

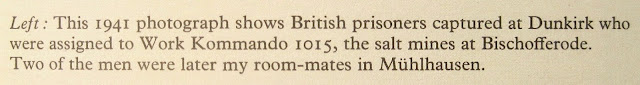

Photo Credit - The Montreal Star, Nov. 9, 1943

The German food was insufficient and tasteless.

It consisted of a steady diet of rotting potatoes, cabbage,

sauerkraut and black bread. This was the daily fare.

Once, we received a type of soup that was 'blood-red'

in colour and had the consistency of blood.

I managed two spoonfuls and shuddered as

the sticky mess stuck to the inside of my mouth.

It was hard to swallow and went down very slowly,

leaving a nauseating effect in the throat and stomach.

Photo Credit - "Ticket to Hell via Dieppe" Page 40

Once a week each man also received a very small

portion of ersatz (substitute or artificial) jam and sugar.

With very careful rationing, we were able to make this last a day.

The daily coffee was also ersatz, usually made from acorns.

Without the Red Cross parcels, we would have gradually starved.

These parcels were supposed to arrive once a week but

often they were not issued. When they did not appear,

the Germans would claim that they had been lost

in air raids by the Allies but, on several occasions, 'Crazy-legs',

the Commandant, was seen eating 'bully-beef' from a British tin.

When the parcels did arrive, it was heaven.

These and the mail, plus the thought of escape,

were the things that kept us going from day to day.

Pages 43 - 44

* * * * *

Photo Credit - "Ticket to Hell" Intro to Chapter 4

A. Robert Prouse attempted an escape from Stalag IXC by slipping into line with a departing work company. The ruse worked to get through the gates and on down the road for a ways. Then "sirens began to wail, announcing our escape."

The Barking of the Dogs

We jumped a fence, left the road

to take to the fields and finally made it

to scrub brush without hearing a shot fired.

Quickly, we forded a small stream and then

climbed a steep railway embankment before

stopping to catch our breath and look back.

The sirens were still screaming

and we could see about fifteen or twenty guards

running through the fields toward the embankment.

As near as we could tell, about three or four of them

were being jerked forward by police dogs.

We took off again, sliding and slipping

down the far side of the embankment.

After running a short way through an open field,

we entered the dense evergreen forest

which had been our immediate destination.

For the next fifteen minutes we never stopped,

proceeding deeper and deeper into the wood

at as fast a pace as we could manage.

Finally, we dropped in sheer exhaustion

and tried to catch our breath. Then we slowly crawled

under the lowest and thickest branches we could find,

each man selecting his own tree for concealment.

It was not too long before

we heard the barking of the dogs.

Fortunately they were not blood hounds

and were only trained to drop a man on sight.

Next we heard intermittent rifle shots as

the guards tried to flush us out of hiding.

I thought for a moment that they had spotted

one of the others but lay motionless anyway.

Then I realized that this was their method

of trying to have us break cover.

It seemed like a lifetime laying there.

I must have died a thousand deaths

as my imagination worked overtime.

All of a sudden I heard

the approach of the guards and dogs.

I ventured a peek and could see jack boots

and dogs' paws no more than six feet from me.

I held my breath and tried desperately to control

the tremor that ran through my body, feeling certain that

the guard would hear the furious pounding of my heart.

Finally, the feet moved off,

gradually receding into the distance.

Others approached and passed but

no one came that close.

It had been 6:00 a.m.

when we first walked through the gates and

we later estimated that it had taken us about

an hour to reach our place of concealment.

It wasn't until around two in the afternoon

that we slowly came out of our hiding place,

looking at each other and grinning with relief

and the first feeling of freedom.

Pages 58 - 59

Mr. Prouse and the small band of escapees made it as far as the German and Czech border before being recaptured. But, if at first you don't succeed...

* * * * *

Before Prouse and others could effectively liberate themselves from captivity, advancing Allied and retreating German forces created a grip that many weakened POWs would not survive. Prouse and many other POWs, however did survive a lengthy, crippling, deadly forced march from one POW camp to another - in an attempt to outpace approaching Allied Forces - and (barely) managed to fall into the lap of liberating troops.

Not a Man Moved. Freedom was Too Near

In the early hours of dawn,

one of the guards told us that the front

was only eight kilometres away.

We could easily believe this,

not only from the air action

but from the sound of heavy shell fire

gradually getting closer and closer.

It was a scary feeling,

being in the middle of the battle,

but at the same time it was exciting

and exhilarating to think of

impending freedom.

There was a sudden commotion

in the Russian enclosure next to ours.

As we watched helplessly,

the Jerry guards rushed in with fixed bayonets

and started to prod the prisoners toward the gates

in an obvious attempt to evacuate the camp

and keep them out of the hands

of the approaching Allies.

There was a lot of screaming

and shouting as the Russians tried

to hang back and elude the prodding guards.

Finally, shooting broke out

and the camp was quickly emptied

except for the dead and wounded

laying in the courtyard.

Our turn came next.

A large group of Germans entered our enclosure.

They commenced the same procedure

of prodding and shouting at us to move out.

Not a man moved.

The whole camp was determined

that this was it: freedom was too near.

The officer in charge of the guards screamed

that either we moved out or we would be shot.

The prisoners held their ground

and glared in defiance.

For a moment there was an ominous silence,

suddenly broken by the unmistakable sound

of approaching tanks.

We knew this was our salvation

and let out a thunderous cheer.

The Jerrys took to their heels,

rushing out of the main gate

and disappearing in full flight.

At 5:05 p.m. on April 11,

the tanks of the American Third Army arrived at the gates of the camp.

We rushed out to greet them and they showered us with cigarettes

and field rations... Before they left, we told them the direction

that the fleeing guards had taken

and asked them to give them hell.

Pages 147-148

Photo Credit - Ticket to Hell via Dieppe.

Editor's final note. The book is highly recommended. I purchased my copy for ten dollars at Attic Books, a used-book store in London, Ontario.

Please link to

Passages: "Ticket to Hell via Dieppe" by A. Robert Prouse (1).

Unattributed Photos GH