"Can We Call You Uncle Jake?"

Photo: Lieut. Koyl, back row, first left. HMS Saunders, N. Africa, 1943]

While combing through issues of The Winnipeg Tribune from 1943, articles appeared that mentioned two Canadian officers connected to Combined Operations during Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily.

References to Lieut. Mullins and Koyl can be found in Sicily, August 16 - 19, 1943 - Pt 16.

Because Lieut. Jake Koyl was mentioned in articles on more than one occasion, as well as in stories written by my father, Doug Harrison (Leading Seaman in RCNVR and Combined Operations), a collection of items has been assembled here to recall some of his varied efforts and responsibilities during his WW2 career.

The earliest reference to Officer Koyl is made during training exercises off the coast of Scotland, near Camp Auchengate (adjacent to RAF Dundonald), located between Irvine and Troon. The time was before their first action, i.e., the cancelled Operation Rutter, mid-July 1942 and Operation Jubilee, Aug. 19, 1942 - both related to the Dieppe Raid.

Harrison writes:

We had an officer named Jake Koyl who was later to become our commander after Lieut. McRae was captured at Dieppe. During the exercise the soldiers became sick, oh so terribly sick. And what happens a long, long way from shore? We run aground.

Koyl says, “Okay, over you go Harrison and Bailey, and together we’ll rock her loose.” We were wearing big heavy duffle coats and sea boots but over we went. After we got her loose, however, Owen left us out there and headed for shore. We fought for high ground against the waves and, weighing nearly a ton, we took off our duffle coats, dropped into holes and had a wonderful time until Owen somehow found us toward morning. The good people at the pub near the place our ALCs docked took us in, gave us blankets, porridge, whiskey, and dried our clothes.

Soon after that we were to get our baptism of fire. Our time of training had come to an end. How would it all show up? (Page 17, "DAD, WELL DONE")

Doug Harrison (left), Al Kirby. Early days in Scotland. (Roseneath?)

Kirby appears in top photo as well. Front row, first on right.

Later in life, my father wrote a longer version of the training incident that left him stranded on a sandbar off the coast of Scotland, and in it he gives Officer Koyl full credit for finding him in the dark. The story (and much more about Canadians in Combined Operations) can be found in St. Nazaire to Singapore: The Canadian Amphibious War, Volume 1, the first of two volumes of stories written, collected and edited by David and Catherine Lewis and Len Birkenes in the early 1990s. The story can also be found in "DAD, WELL DONE", my father's Navy memoirs.

Link here to St. Nazaire.... Volume 1 for more information.

The longer version of Harrison's story follows:

Exercise Schuyt 1: Marooned on a Submerged Sand Bar

It was so damn dark. “Keep closed up!” I can still hear (Officer) Andy Wedd’s voice to this day. (I am glad I saw him shortly before his death.)

At the night exercise the time of arrival was midnight. The crew was Koyl, Art Bailey, Stoker Lank and his pail (Willard Lank was always chewing kelp), and myself, with a full complement of English soldiers. Believe me, these fellows were sick soldiers. Bailey and I lashed ourselves down as best we could and emptied the helmets as the soldiers handed them up. Destination or landing, I don’t remember. Troon (Scotland)? I can remember two perimeter lights vaguely in the distance.

We were perhaps headed south and it was rough (all of this is true). Our craft ran aground on a sand bar. Koyl ordered everybody - Bailey and I and himself - overboard to look or tread for deeper water. First we tried rocking the craft in conjunction with the motors. No luck. Wandering in sea boots, underwear, duffel coats, I fell into deeper water (which wasn’t too cold fortunately) and hollered, “Over here, sir!”

So we worked our asses off to free the ALC and we were successful. The soldiers helped to rock the craft. Koyl’s fuming, “We are going to be late!” And he is flotilla commander. Bailey and Koyl were able to get aboard. I wasn’t and they drove off and left me out in the water.

I was scared. But I felt I knew Mr. Koyl. I discarded all my clothing but uniform pants and underwear, found a sandbar and waited it out. They made their landing eventually but.... How is he going to find me (this is unbelievable)? I thrashed my arms, swam on my back for short stints to maintain circulation and after an eternity I saw an Aldis lamp blinking.

Motors were cut, then revved up, then cut. Koyl had a fair idea perhaps but I don’t know how he knew where to locate me. Eventually our voices came reasonably close together. I was caught in the light of the Aldis lamp and picked up after one and a half or two hours waiting. My hands were all wrinkled. I felt all in.

When we returned to Irvine (a few miles north of Troon), Koyl, Bailey and I hurried to a local pub (now known as the Harbour Light*). We were given hot porridge, rum and our clothes were taken to be dried and we were wrapped in blankets. All of this help came from ladies. It was late afternoon before we left the pub - Royal Sovereign or King George? I was a very lucky fellow. In the darkness Koyl and Bailey took awhile before they missed me. I didn’t really know what went amiss but the fact that the landing had to be made on time was uppermost in Koyl’s mind.

Full caption with photo: The Public House, the King’s Arms, where the Skinner family revived Doug Harrison and the rest of Jack Koyl’s boat crew. They used hot drinks, hot porridge and hot blankets. [Pub’s name has been changed, perhaps in honour of the occasion to “The Harbour Lights”]

*Editor’s Note: I believe the photo and caption above were added to my father's story by David Lewis, creator of St. Nazaire to Singapore Vol. 1, to help clarify the name of the Scottish pub.

I add this note for the same purpose: I visited Irvine, Scotland in October, 2014 and visited both the long-standing Harbour Lights (formerly known as the Victoria Hotel) and King's Arms Hotel. The Harbour Lights was formerly owned by John and Mary Burns and the King's Arms Hotel, owned in 2014 by the Scott family, was formerly owned by the Skinners, a family both mentioned by David Lewis and my father (in another story) as the ones who helped out the tired ALC crew. So, of all the names tossed about, the King's Arms Hotel is definitely the best fit, and its name was never changed "in honour of the occasion." (Pages 51-52, "DAD, WELL DONE")

In a response to a Canadian Combined Ops Questionnaire (circulated in 1993-1996), my father writes (in part) the following re Lieut. Koyl:

I was fond of Mr. Koyl who said, “Don’t bother me with the petty stuff Mr. Wedd. Let’s get the job done and go home.”

I asked him one day, “Sir, do you mind us calling you Uncle Jake?”

“No Harrison, I don’t. On the contrary, I’m honoured.”

Harrison mentions Koyl briefly in a passage related to the last days of Combined Operations in Sicily, August 1943, before the 80th and 81st Canadian Flotillas of landing craft sailed for Malta for rest and repair:

Harrison mentions Koyl briefly in a passage related to the last days of Combined Operations in Sicily, August 1943, before the 80th and 81st Canadian Flotillas of landing craft sailed for Malta for rest and repair:

Koyl is mentioned again, briefly, when Canadians in landing crafts arrived in Malta, August, 1943:

When my friends returned from Sicily in their landing craft, I was waiting for them at the bottom of the cement steps. Our commanding officer Lt/Comdr Koyl and a few hands disappeared for awhile and when they returned they were weighted down with kit bags of parcels and mail.

The blues disappeared and quietness settled in as every one of us, in a different posture, chewed on an Oh Henry bar and read news from home. The war wasn’t so bad after all. We shared with anyone who hadn’t received a parcel; no one went hungry. We feasted on chocolate bars, cookies, canned goods and the news. (Page 112, "DAD, WELL DONE")

In the book Combined Operations by Londoner Clayton Marks (available by contacting Editor, G. Harrison), one will read a lengthy report about the actions undertaken and the progress made by Canadians in Combined Ops, including their time in Sicily in 1943.

Lieut. Cmdr. Koyl's report begins as follows:

The idea of Combined Operations is not by any means a new one but merely the bringing back to life of an old war idea. After the evacuation of Dunkerque, Combined Operations began to take on a definite plan under the leadership of Sir Roger Keyes who was appointed Chief of Combined Operations (C.C.O.) on July 17, 1940. This Junior branch of the Navy had facing it all the problems and difficulties which a new idea or branch encounters in a service built up on centuries of tradition. This was most unfortunate as it could not enjoy the necessary co-operation to build itself up to the degree of efficiency which would be required for the tasks that lay ahead.

Up until and as late as January 1943, Flotilla Officers who were then building up new organizations, could not procure even sufficient craft to train their men for actual operations. It has been known for a Flotilla Officer to approach an enemy coast not ever having seen the majority of his men in training and with the full realization that they were not capable of doing their task in a competent manner. Conditions improved shortly after this, and it was sincerely hoped that the new year would do away with the utter confusion and chaos of 1942. This is not a criticism of the Combined Operations policy during that period but it is merely being mentioned to bring home the fact that several groups of Canadian volunteers were face to face with conditions which were discouraging.

In the early days of Combined Operations, a sprinkling of Canadian Officers who were on loan to the R.N. were present on some of the more important raids, or should one say raids that were released to the press; Lofoten, Boulogne, St. Nazaire. In the latter part of 1941, the Canadian Navy committed itself to send on loan to the Royal Navy, 50 Officers and 500 Ratings, to form Canadian Flotillas. The Officer material for these first two units were chosen from the Naval Colleges H.M.C.S. "ROYAL ROADS" and H.M.C.S. "KINGS". All men joining this band were to be volunteers and unmarried. Little information could be gathered on the subject as a cloak of mystery and "hush hush" covered the whole picture.

In January, 1942 fourteen Officers and ninety-six Ratings sailed from Canada for the U.K. in the Volendam knowing nothing of what lay ahead but looking forward to a rather exciting life. On arrival in the U.K. they began a course of training which lasted two months, most of this training being LCAs, Landing Craft Assault, and LCMs, Landing Craft Mechanized. By the end of April they were split up into two operational Flotillas.

The first operational call received was in early June when they sailed away from their base to take part in some operation, but this was cancelled and all were ordered to return to base. These periods of suspense were most trying on the morale of all men as during these periods of waiting, sometimes lasting over two months, they were posted to routine camp duties.

The first opportunity for action came with the Dieppe raid. Though not operating as Canadian units, Officers and men were intermingled with R.N. Flotillas and much valuable experience was gained. (Pages 173-174, Combined Operations)

The complete report by Koyl can be found at Memoirs re Combined Operations - Lt. Cdr. J. E. Koyl

Canadians approach Malta, Aug. 1943, in Landing Crafts, Mechanized

Photo from the collection of Joe Spencer, RCNVR, Comb. Ops.

Lieut. Cmdr. Koyl's report begins as follows:

The idea of Combined Operations is not by any means a new one but merely the bringing back to life of an old war idea. After the evacuation of Dunkerque, Combined Operations began to take on a definite plan under the leadership of Sir Roger Keyes who was appointed Chief of Combined Operations (C.C.O.) on July 17, 1940. This Junior branch of the Navy had facing it all the problems and difficulties which a new idea or branch encounters in a service built up on centuries of tradition. This was most unfortunate as it could not enjoy the necessary co-operation to build itself up to the degree of efficiency which would be required for the tasks that lay ahead.

Up until and as late as January 1943, Flotilla Officers who were then building up new organizations, could not procure even sufficient craft to train their men for actual operations. It has been known for a Flotilla Officer to approach an enemy coast not ever having seen the majority of his men in training and with the full realization that they were not capable of doing their task in a competent manner. Conditions improved shortly after this, and it was sincerely hoped that the new year would do away with the utter confusion and chaos of 1942. This is not a criticism of the Combined Operations policy during that period but it is merely being mentioned to bring home the fact that several groups of Canadian volunteers were face to face with conditions which were discouraging.

In the early days of Combined Operations, a sprinkling of Canadian Officers who were on loan to the R.N. were present on some of the more important raids, or should one say raids that were released to the press; Lofoten, Boulogne, St. Nazaire. In the latter part of 1941, the Canadian Navy committed itself to send on loan to the Royal Navy, 50 Officers and 500 Ratings, to form Canadian Flotillas. The Officer material for these first two units were chosen from the Naval Colleges H.M.C.S. "ROYAL ROADS" and H.M.C.S. "KINGS". All men joining this band were to be volunteers and unmarried. Little information could be gathered on the subject as a cloak of mystery and "hush hush" covered the whole picture.

In January, 1942 fourteen Officers and ninety-six Ratings sailed from Canada for the U.K. in the Volendam knowing nothing of what lay ahead but looking forward to a rather exciting life. On arrival in the U.K. they began a course of training which lasted two months, most of this training being LCAs, Landing Craft Assault, and LCMs, Landing Craft Mechanized. By the end of April they were split up into two operational Flotillas.

Effingham Division, Halifax, 1941. First draft of volunteers for Combined Ops.

My father sits in front row, third from left.

Canadians at first training camp, Northney on Hayling Island, England. Jan. 1942

L-R: Adlington, Spencer, Rose, Harrison, Bradfield, Linder, Watson, Jacobs.

Canadians learn how to handle ALCs and LCMs in England and Scotland, 1942

Jim and Ray, of Effingham Div., at HMS Quebec, Inveraray, 1942

From collection of Joe Spencer.

The first operational call received was in early June when they sailed away from their base to take part in some operation, but this was cancelled and all were ordered to return to base. These periods of suspense were most trying on the morale of all men as during these periods of waiting, sometimes lasting over two months, they were posted to routine camp duties.

The first opportunity for action came with the Dieppe raid. Though not operating as Canadian units, Officers and men were intermingled with R.N. Flotillas and much valuable experience was gained. (Pages 173-174, Combined Operations)

The complete report by Koyl can be found at Memoirs re Combined Operations - Lt. Cdr. J. E. Koyl

Jake Koyl, other Canadian officers and members of the lower ranks receive some mention in newspaper articles found in digitized issues of The Winnipeg Tribune from 1943.

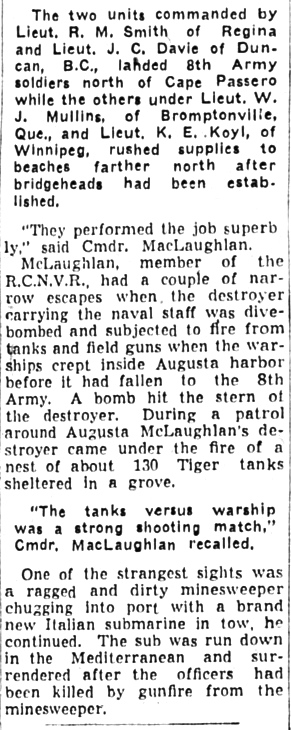

One mention of Lieut. Mullins and Lieut. Koyl is found in an August 18, 1943 article by The Canadian Press entitled "Canadian Tars Did 'Grand Job' Landing Troops."

We read:

The full article can be found at "Canadian Tars Did 'Grand Job'..."

Jake Koyl is also mentioned earlier in a July 27, 1943 Tribune article by The Canadian Press entitled "Practice Made Perfect For R.C.N. At Sicily".

We read, in part:

The article continues with the following about the Canadian unit's two officers:

We read:

Jake Koyl is also mentioned earlier in a July 27, 1943 Tribune article by The Canadian Press entitled "Practice Made Perfect For R.C.N. At Sicily".

We read, in part:

The article continues with the following about the Canadian unit's two officers:

(Dispatches from Allied Headquarters in North Africa said it was estimated 500 Canadian naval men took part in the Sicilian landings as members of the R.C.N., the Royal Navy, and Combined Operations units.)

The full article can be found at "Practice made Perfect...".

My Dad may well have considered Jake Koyl his favourite officer. While writing weekly columns in the early 1990s for his hometown newspaper, the Norwich Gazette, my father wrote the following column about the man:

LT/COMDR JACOB KOYL EARNED MY RESPECT

In the spring of 1942, I was stationed for a short time in navy barracks at Roseneath, Scotland. As we Canadian sailors departed from Roseneath I was detailed to work on a baggage party by Leading Seaman Bowen. I told him I wasn’t fussy about handling kit bags and hammocks, to which he replied, “Fussy or not, just get at it and lend a hand.”

After a short argument I refused (which is bad, real bad) and he took me to have a chat with our huge, no-nonsense commanding officer Lt/Comdr Jacob Koyl, later to be known as Uncle Jake. L/S Bowen explained his case about my refusal to Mr. Koyl. With that, Bowen was dismissed and the commanding officer laid his big hand on my shoulder and started to recite, without benefit of the navy book, King Rules (KR) and Admiralty Instructions (AI) about the seriousness of refusing an order.

I knew I was in for rough seas as he continued to expound, his big hand bowing my shoulder. Lt/Comdr Koyl wore navy boots so big they looked like the boxes they came in. I know, because I was looking at them; this officer didn’t walk, he plodded.

At the end of his recitation, this man, who later had the undying respect of every Canadian sailor under his command, said to me, “I am not going to punish you so it shows on your records. All I want my officers and men to do is work together so we can get the job done over here and we can all go home, and that includes baggage party.”

“Harrison!”

“Yes sir!”

“You will be stowing kit bags and hammocks today, and every time a baggage party is required, you will be front and centre, and I’ll be standing by with my little eye on you.”

With that, he took his big hand off my shoulder, I straightened up, saluted, and said a little prayer. I was one lucky sailor; he could have come down much harder on me. The Canadian naval officer had played defense for the old New York Rovers farm team of the New York Rangers in the old six team NHL of 1939 - 40. I remember the dressing down he gave me and how his fingers sank into my shoulder to emphasize a point. A few years later, I remember talking to my sons in the exact same way.

Our particular group of Canadian sailors moved from ship to ship often and our numbers steadily grew until there were approximately 250, and whenever we moved I was front and centre and, true to his word, Mr. Koyl was not too far away (smiling). Each time I was baggage party I learned a little more about KR and AI. I soon got to know over 200 kit bags personally and my muscles got larger like you wouldn’t believe. My knuckles were skinned on kit bag padlocks and my hands got burned on hammock lashings, and although I rose in rank under Mr. Koyl’s instruction, I remained baggage party. Badly bowed, but unbeaten, I had this job down to a science.

Mr. Koyl enjoyed every minute of it (I knew every wrinkle in his uniform), and once in awhile he heaped a few coals of fire on my head by thanking me for improving the time it took, and if there were medals struck for most improved sailor of the year and baggage party, he would be more than happy to recommend me. Yes sir! I never let on I heard his bantering; he had earned my respect as the hammocks flew and kit bags were piled high.

Late June, 1943 was the last time I helped move that huge mound of baggage. We were in Dejehli, Egypt and we stowed them in a wonderfully clean army building there. I put a navy padlock on the door (I’m kingpin now), the baggage party walked to a waiting truck and none of us ever saw our gear again. Our clothing, photos, souvenirs, everything we owned, went missing.

It took a lot of years, but the baggage episode did have a happy ending for me. In August, 1990 Leading Seaman Harrison visited Leading Seaman Bowen in Ottawa and L/S Bowen was detailed to carry my baggage from the car to the hotel room. Who was it that said, “It’s a long road that has no turning”?

Much decorated Lt/Comdr Jacob Koyl died in November, 1987 and was buried where he had earned his honours - at sea.

Please link to Articles: Sicily, August 16 - 19, 1943 - Pt 16.

At the end of his recitation, this man, who later had the undying respect of every Canadian sailor under his command, said to me, “I am not going to punish you so it shows on your records. All I want my officers and men to do is work together so we can get the job done over here and we can all go home, and that includes baggage party.”

“Harrison!”

“Yes sir!”

“You will be stowing kit bags and hammocks today, and every time a baggage party is required, you will be front and centre, and I’ll be standing by with my little eye on you.”

With that, he took his big hand off my shoulder, I straightened up, saluted, and said a little prayer. I was one lucky sailor; he could have come down much harder on me. The Canadian naval officer had played defense for the old New York Rovers farm team of the New York Rangers in the old six team NHL of 1939 - 40. I remember the dressing down he gave me and how his fingers sank into my shoulder to emphasize a point. A few years later, I remember talking to my sons in the exact same way.

Our particular group of Canadian sailors moved from ship to ship often and our numbers steadily grew until there were approximately 250, and whenever we moved I was front and centre and, true to his word, Mr. Koyl was not too far away (smiling). Each time I was baggage party I learned a little more about KR and AI. I soon got to know over 200 kit bags personally and my muscles got larger like you wouldn’t believe. My knuckles were skinned on kit bag padlocks and my hands got burned on hammock lashings, and although I rose in rank under Mr. Koyl’s instruction, I remained baggage party. Badly bowed, but unbeaten, I had this job down to a science.

Mr. Koyl enjoyed every minute of it (I knew every wrinkle in his uniform), and once in awhile he heaped a few coals of fire on my head by thanking me for improving the time it took, and if there were medals struck for most improved sailor of the year and baggage party, he would be more than happy to recommend me. Yes sir! I never let on I heard his bantering; he had earned my respect as the hammocks flew and kit bags were piled high.

Late June, 1943 was the last time I helped move that huge mound of baggage. We were in Dejehli, Egypt and we stowed them in a wonderfully clean army building there. I put a navy padlock on the door (I’m kingpin now), the baggage party walked to a waiting truck and none of us ever saw our gear again. Our clothing, photos, souvenirs, everything we owned, went missing.

It took a lot of years, but the baggage episode did have a happy ending for me. In August, 1990 Leading Seaman Harrison visited Leading Seaman Bowen in Ottawa and L/S Bowen was detailed to carry my baggage from the car to the hotel room. Who was it that said, “It’s a long road that has no turning”?

Much decorated Lt/Comdr Jacob Koyl died in November, 1987 and was buried where he had earned his honours - at sea.

Please link to Articles: Sicily, August 16 - 19, 1943 - Pt 16.

Unattributed Photos GH