Starring Scott Young and Sholto Watt

Photo Credit - The majority of news articles, photos, cartoons and ads are

from The Montreal Star microfilm at University of Western Ontario

(UWO), London, Ontario

One headline above (left) tells us that the "War (is) Lost For Huns" while another headline above (right) tells us the "Allies Meet Toughest Terrain Yet." Russia's advances against the Germans would be accompanied by some cheering, while Allied forces in Italy would be heard grinding their teeth at slow, oft-times discouraging progress.

As would be expected, The Montreal Star will report good and not-so-good reports from different corners of the world, and we will continue to learn how extensive, expensive and weighty was World War II.

That being said, I am happy to report that two articles are included in this offering by Canadian war correspondent Scott Young, father of well-known singer-songwriter Neil Young. And with a note of relief I can say - again, quite happily - I have found a lengthy and informative article by The Star's war correspondent, Sholto Watt, and will present it below (about a dozen items down).

Watt's previous report came from Sicily, several weeks after Canadians in Combined Operations had left Sicily to go to Malta for rest, recuperation and the job of repairing their landing crafts. The report that follows comes from Malta, also several weeks after the Canadians and their landing craft left Malta to start the business of running troops and war materiel from Sicily to Reggio di Calabria (i.e., to the toe of Italy) in their flotilla of LCMs (landing craft, mechanised).

Will Mr. Watt make his way to Italy soon and hitch a ride with those Canadians? I am hoping he will. Until I find out one way or the other I will continue to present news from the front, along with other details re the times.

As would be expected, The Montreal Star will report good and not-so-good reports from different corners of the world, and we will continue to learn how extensive, expensive and weighty was World War II.

That being said, I am happy to report that two articles are included in this offering by Canadian war correspondent Scott Young, father of well-known singer-songwriter Neil Young. And with a note of relief I can say - again, quite happily - I have found a lengthy and informative article by The Star's war correspondent, Sholto Watt, and will present it below (about a dozen items down).

Watt's previous report came from Sicily, several weeks after Canadians in Combined Operations had left Sicily to go to Malta for rest, recuperation and the job of repairing their landing crafts. The report that follows comes from Malta, also several weeks after the Canadians and their landing craft left Malta to start the business of running troops and war materiel from Sicily to Reggio di Calabria (i.e., to the toe of Italy) in their flotilla of LCMs (landing craft, mechanised).

Will Mr. Watt make his way to Italy soon and hitch a ride with those Canadians? I am hoping he will. Until I find out one way or the other I will continue to present news from the front, along with other details re the times.

Below we see a grainy photograph depicting hospital care for 'wounded commandos', including Canadian Walter Pace from Medicine Hat, Alta.

Note to self: Google Canadians in Commando units

Scott Young travelled to Sicily in the summer of 1943 and wrote several articles about events related to Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily. Some can be found on this blog, and are from The Winnipeg Tribune. The following are striking in their difference re subject matter and origin:

The next article by Mr. Young was found on the same editorial page. Two for the price of one, I say:

General Montgomery, or Monty, could always be counted on to express an opinion:

While Monty's 8th Army made gains - slowly, oft-times at significant cost in human lives - so to did the Russians on the Eastern Front, part of which bordered the Dnieper River:

When I saw that 'Foggia Airfields' were mentioned in the September 27 headlines, I took note. Foggia was under observation by RAF and RCAF pilots in their Spitfires, and was mentioned in the flight log of one Canadian pilot from Chatham, Ontario, a city one-hour's drive from my front door. Information about the pilot, FO John Vasicek, is mentioned in an earlier entry.

Canadian war correspondent Ross Munro surely travelled to the toe of Italy's boot with the Canadians manning their own flotilla of landing crafts (80th Flotilla). He writes about "the 400-mile advance Canadian troops made from the Reggio beaches". He may have embarked from an area just north of Messina, Sicily, where Canadians in Combined Ops bunked down in war-worn and damaged houses ( one had no roof says my father) not far from their LCMs. If Mr. Munro disembarked on the opposite side of the Strait of Messina where supplies were being dropped off in Reggio, a Canadian sailor likely dropped the ramp for him. (I'd love to see his notes or journals!)

While Ross Munro connected with Canadian readers about the advance of Canadian troops, he and the army were supplied by a well-organized transport system. A week or so after the invasion of Italy (Sept. 3 in Reggio; Operation Baytown), the ferrying of all war materiel would have become a bit more routine for the men of the barges, life would have become a bit more normalized.

In memoirs my father writes about that time:

THE INVASION OF ITALY

It was no different touching down on the Italian beach at Reggio Calabria at around midnight, September 3, 1943 than on previous invasions. Naturally we felt our way slowly to our landing place. Everything was strangely quiet and we Canadian sailors were quite tense, expecting to be fired upon, but we touched down safely, discharged our cargo and left as orderly and quietly as possible.

In the morning light on our second trip to Italy across seven miles of the Messina Straits we saw how the Allied artillery barrage across the straits had levelled every conceivable thing; not a thing moved, the devastation was unbelievable and from day one we had no problems; it was easy come, easy go from Sicily to Italy.

Can someone help with a translation?? "Operation Baytown -

Allied troop barges (landing craft) at Reggio Calabria?"

I remember one of the many refugees of war, a barefoot lady dressed in a black sleeveless dress, carrying a huge black trunk on her head. I suppose it contained all her earthly belongings or it was very dear to her, and she walked along the coastal road back toward Reggio, to what, I’ll never know. I couldn’t have carried that load.

Our living quarters was a huge Sicilian home and some nights I slept on my hammock on a beautifully patterned marble floor. However, since that was a hard bunk I sometimes slung my hammock, covered with mosquito netting, between two orange trees in the immense yard.

Canned food was quite plentiful now and several young Sicilian boys, quite under-nourished, came begging for handouts, especially chocolota, as they called our chocolate bars.

I took a boy about 11 years old under my wing when off duty. In one corner of the yard was a low, square, cement-walled affair complete with a cement floor, tap and drain hole. It was here I introduced “Peepo” to Ivory soap, Colgate toothpaste and hair tonic for his short, shiny, ringletted black hair. My name was “Do-go” which I am still called today at navy reunions, and this boy really shone when I had finished his toilet. Peepo wasn’t too keen on soap and water and it certainly was obvious, but not for long.

I tried to learn some of his language, and he mine (the Canadian Marina). Although we were from countries thousands of miles apart, the war had brought us together and we got along famously. He and I also wandered about Messina. I went with Peepo to meet his Mamma. I took some canned food, chocolota and compost tea, a complete tea in a can exactly like a sardine can, with a key attached as well. Although the lad’s mother was forty-ish, she appeared older. Over a cup of tea, and with difficulty, Mrs. Guiseppe said she would do some laundry for me, and mending.

*Editor's note: I would be surprised if my father saw the Adriatic Sea while working aboard landing crafts between Sicily and Reggio. However, he would have heard about it.

"Dad, Well Done", Page 116

Now, a house on a cliff top in September - even with no roof - was certainly a step up from his accommodations in July, i.e., a limestone cave in Sicily known as The Savoy.

Below is a very thorough description of the "home of a quarter-million people, Malta" that survived WW2 by a thread. Mr. Watt, correspondent for The Montreal Star, is the key reason for my current research, and I am hoping to soon find more articles that focus on his time in Italy, especially how he got there. E.g., Did he go by Canadian landing craft? And if so, did he mention a few names of the sailors on board?

The following photo is quite grainy but upon close inspection one can see troops or sailors standing on the open ramp of the Landing Ship, Tank, aka LST. These are a variation on the theme of landing craft and are likely more efficient than earlier LCTs (landing craft, tank) that had a flat bottom from stem to stern I believe.

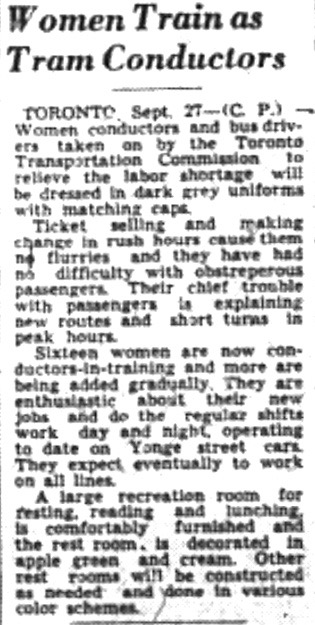

From E-Boats in the English Channel to Canadian jam ("Much More Needed"), The Star keeps us well informed:

More will follow from Italy in the near future.

Unattributed Photos GH