"The red-headed boy went on running... his eyes glaring whitely wildly..."

(Drawing by Gord Harrison)

And in many other passages found within the hefty pages of Writers On World War II the misery and emotions and many details related to bombings, and as well subsequent comebacks and triumphs, are ably shared.

Below are a few excerpts and poignant passages from said text:

London's Organic Power (1940)

Parks suddenly closed because of time-bombs...

Those rendered homeless sat where they had been sent;

or, worse, with the obstinacy of animals retraced their steps

to look for what was no longer there.

Most of all the dead, from mortuaries, from under cataracts of

rubble, made their anonymous presence - not as today's dead

but as yesterday's living - felt through London. Uncounted,

they continued to move in shoals through the city day, pervading everything

to be seen or heard or felt with their torn-off senses,

drawing on this tomorrow they had expected -

for death cannot be so sudden as all that.

Absent from the routine which had been life,

they stamped upon that routine their absence -

not knowing who the dead were you could not know

which might be the staircase somebody for the first time

was not mounting this morning,

or at which street corner the newsvendor missed a face,

or which trains and buses in the homegoing rush

were this evening lighter by at least one passenger.

These unknown dead

reproached those left living not by their death, which might

any night be shared, but by their unknownness,

which could not be mended now.

Who had the right to mourn them,

not having cared that they had lived?

So, among the crowds still eating, drinking, working,

travelling, halting, there began to be an instinctive movement

to break down indifference while there was still time.

The wall between the living and the living became less solid

as the wall between the living and the dead thinned.

In that September transparency people became transparent,

only to be located by the just darker flicker of their hearts.

Strangers saying "Goodnight, good luck," to each other at street corners,

as the sky first blanched, then faded with evening, each hoped

not to die that night, still more not to die unknown.

By Elizabeth Bowen, from The Heat of the Day, pages 68 - 69

Hitler Came At Last

We drilled at first with broomsticks* owing to the dearth of rifles,

then an actual rifle appeared and was handed around the square,

though our platoon hadn't much time to learn its mechanism

before a runner came to attention in front of our sergeant saying:

"Please sar'nt, our sar'nt in No. 8 says could we have the rifle for a

dekko over there 'cause none of our blokes so much as seen one yet."

[*broomsticks were familiar to Canadian sailors during initial training in Combined Operations as well. "We were issued brooms for guard duty in some cases at HMS Northney (Hayling Island, southern England, early 1942) sometimes a rifle with no ammunition, and they were expecting a German invasion," writes my father in Navy memoirs.]

Doug Harrison, early recruit in RCNVR, Combined Operations,

Found in St. Nazaire to Singapore, Vol. 1 (pg. 183), by David. J. Lewis

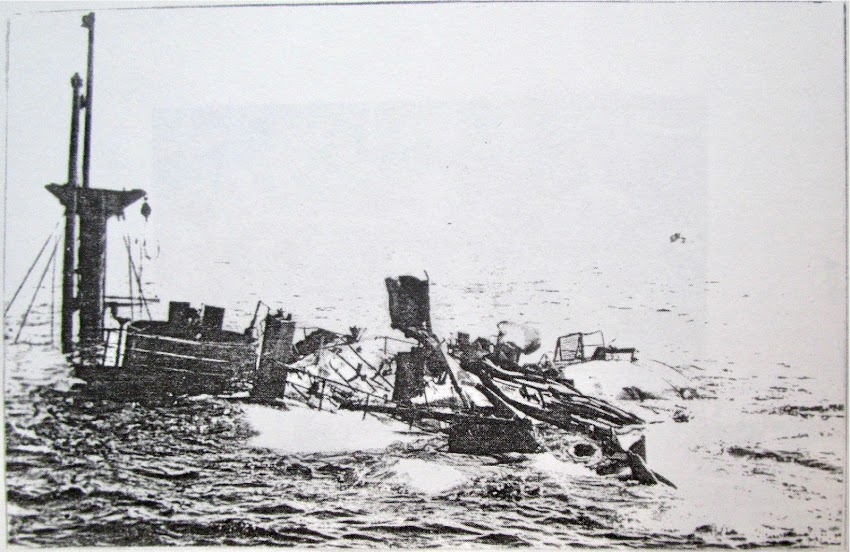

Luftwaffe attacks ships off the coast of Sicily. Imperial War Museum

Hitler Came At Last, continues:

There were no NCOs present, still less an officer; we dashed

to the side doorway, got jammed in the entrance, then threw ourselves

flat beneath a whitewashed wall outside as jerry zoomed over low,

chips of whitewash flew; and we heard for the first time in earnest

the DUH-DUH-DUH of the machine gun

that had been so often mimicked in jest...

...more bombs whistled down, one sounding like a direct hit;

and the Nazi plane returned, circling silver and so high above our heads

it could hardly be seen; voices from adjoining trenches shouted:

"Where the bleeding bloody officers?" and "Why'nt we got tin hats?"

while somebody shrilled hysterically: "Shut your row, he'll hear us.

he'll hear us I tell you, shut your bleeding row."

The Jerry pilot didn't hear them and soon ceased to hear anything at all,

for he flew away to be caught in the Bournemouth barrage

and shot down in flames so we were later told.

By Julian MacLaren-Ross, A Big Lake, pages 86 - 87

Some Canadian members of Combined Operations suffered their first air attack on their way from HMS Quebec (Combined Operations No. 1 Training camp, near Inveraray, Scotland) to the Bournemouth and Portsmouth area in southern England prior to the Dieppe Raid. One sailor tells this tale:

A TASTE OF DIEPPE, 1942

We went from Irvine to H.M.S. Quebec, then to H.M.S. Niobe andthen aboard the oil tanker Ennerdale at Greenock in late April, 1942.

Our barges were loaded on the ship too, by use of booms and winches.

I do recall that before leaving Greenock one of the ship’s crew said to me,

“I wish we weren’t going on this trip, matey.” When I asked why he said,

“‘Cause we got a bloody basinful last time!” We got our basinful this time too.

During the trip down the west coast of England it seems we pulled into

an Irish seaport one night; however, farther down the coast of England

we headed south past Milford Haven, Wales, and all was serene.

We usually had a single or maybe two Spitfires for company. There were

eight ships in the convoy; we were the largest, the rest were trawlers.

Of course, the Spitfires only stayed until early dusk,

then waggled their wings and headed home.

On June 22, 1942, my mother’s birthday, O/D Seaman Jack Rimmer

of Montreal and I were reminiscing on deck. We must remember

there was daylight saving time and war time, and to go by the sun setting

one never knew what time it was. Jack and I were feeling just a little homesick

- not like at first - and it was a terribly hard feeling to describe then.

As we can see, Jack Rimmer survived the first bombing. He is now aboard

HMS Keren on his way to Operation HUSKY (Sicily), summer 1943

Provenance - Doug Harrison, RCNVR, Combined Ops

A TASTE OF DIEPPE, 1942 continues:

Our Spitfire waggled his wings and kissed us goodnightthough it was still quite light, and no sooner had he left when

‘action stations’ was blared out on the Klaxon horn.

Eight German JU 88s came from the east, took position in the sun and

attacked us from the stern. It was perhaps between eight and nine o’clock

because I had undressed and climbed into my hammock next to Stoker Fred Alston.

When the Klaxon went everybody hit the deck and tried to dress,

and being the largest ship, we knew we were in for it.

I got my socks on, put my sweater on backwards and got the suspenders

on my pants caught on the oil valves. I was hurrying like hell and nearly

strangled myself - scared to death. They needed extra gunners so Lloyd Campbell

The gun crew on the foc’sle of the ship was knocked clear off

the gun by the concussion and fell but were only bruised.

The attack was short and sweet but it seemed an eternity.

A near miss had buckled our plates and we lost all our drinking water.

I ventured out on deck immediately and picked up bomb shrapnel as big

as your fist. I noticed the deck was covered with mud from the sea bottom.

I kept the shrapnel as a souvenir along with many other items I had

but, alas, they were all lost in Egypt.

We arrived at Cowe (Isle of Wight) the next day

with everyone happy to be alive and still shaking.

It indeed had been a basinful.

Incidentally, two German 88s were shot down.

two planes shot down during the course of the war;

one at Dieppe and one at Sicily. Both were low flying bombers.

His weapon was a strip Lewis 303.

By Doug Harrison, "Dad, Well Done," pages 19 - 20

In the book Writers on World War II are words from an author who "went directly from Trinity College, Oxford, into the RAF." Excerpts from "his famous account of the Battle of Britain" follow:

I Knew He Was Mine

We ran into them at 18,000 feet,twenty yellow-nosed Messerschmitt 109s, about 500 feet above us.

Our squadron strength was eight, and as they came down

on us we went into line astern and turned head on to them.

Brian Carbury, who was leading the section, dropped the nose

of his machine and I could almost feel the leading Nazi pilot

push forward on his stick to bring his guns to bear.

At the same moment Brian hauled hard back on his control stick

and led us over them in a steep climbing turn to the left.

In two vital seconds they lost their advantage.

I saw Brian let go a burst of fire at the leading plane,

saw the pilot put his machine into a half roll,

and knew he was mine. Automatically, I kicked

the rudder to the left to get him at right angles,

turned the gun-button to "Fire," and let go

in a four-second burst with full deflection.

He came right through my sights and I saw

the tracer from all eight guns thud home.

For a second he seemed to hang motionless; then a

jet of red flame shot upward and he spun out of sight.

For the next few minutes I was too busy

looking after myself to think of anything,

but when, after a short while, they turned

and made off over the Channel,

and we were ordered to our base,

my mind began to work again.

It had happened.

My first emotion was one of satisfaction, satisfaction at a job adequately

done, at the final logical conclusion of months of specialized training.

And then I had a feeling of the essential rightness of it all.

He was dead and I was alive; it could so easily have been the

other way round; and that somehow would have been right too.

I realized in that moment just how lucky a fighter pilot is.

He has none of the personalized emotions of the soldier,

handed a rifle and bayonet and told to charge.

He does not even have to share the dangerous emotions

of the bomber pilot who night after night must experience

that childhood longing for smashing things.

The fighter pilot's emotions are those of a duelist -

cool, precise, impersonal. He is privileged to kill well.

For if one must either kill or be killed, as now

one must, it should, I feel, be done with dignity.

Death should be given the setting it deserves; it should never

be a pettiness; and for the fighter pilot it never can be.

From this flight Broody Benson did not return...

.... Often there would be a telephone-call from some pilot to say that

he had made a forced landing at some other aerodrome, or in a field.

But the telephone wasn't always so welcome.

It would be a rescue squad announcing the number of a crashed machine;

then Uncle George would check it, and cross another name off the list.

At that time, the losing of pilots was somehow extremely impersonal;

nobody, I think, felt any great emotion - there simply wasn't time for it.

By Richard Hillary, The Last Enemy, pages 94 - 95

From a battle in the air we turn now to a famous battle - and the sinking of the Bismarck - upon cold, grey seas:

It Was Not a Pretty Sight

There she was at last,

the vessel that these past six days had filled our waking thoughts,

been the marrow of our lives. And, as the rain faded, what a ship!

Broad in the beam, with long raked bow and formidable superstructure,

two twin 15-inch gun turrets forward, two aft, symmetrical, massive,

elegant, she was the largest, most handsome warship I, or any of us,

had ever seen, a tribute to the skills of German shipbuilding.

Now there came flashes from her guns and those of King George V.

The final battle had begun.

In all my life I doubt if I will remember

another hour as vividly as that one...

There was the somber blackness of Bismarck and the gray of the British ships,

the orange flashes of the guns, the brown of the cordite smoke,

shell splashes tall as houses, white as shrouds.

It was a lovely sight to begin with, wild, majestic as one of

our officers called it, almost too clean for the matter at hand...

And who was going to win? None of us had any illusions

about the devastating accuracy of Bismarck's gunfire. She had

sunk Hood with her fifth salvo, badly damaged Prince of Wales,

straddled Sheffield and killed some of her crew the evening before, and

hit an attacking destroyer in the course of the previous pitch-black night.

But there were factors we had not reckoned with:

the sheer exhaustion of her crew who had been at action stations

for the past week, the knowledge as they waited through that long,

last dreadful night that the British Navy was on its way to exact

a terrible revenge, that they were virtually a sitting target.

Rodney was straddled with an early salvo but not hit,

then with her firing divided, Bismarck's gunnery sharply fell off.

But that of Rodney and King George V steadily improved.

As they moved in ever closer, we observed hit after hit.

The hydraulic power that served the foremost turret

must have been knocked out early, for the two guns were

drooping downward at maximum depression, like dead flowers.

The back of the next turret was blown over the side and one

of its guns, like a giant finger, pointed drunkenly at the sky.

A gun barrel in one of the two after turrets had burst,

leaving it like the stub of a peeled banana...

Through holes in the superstructure and hull

we could see flames flickering in half a dozen places.

But still her flag flew: still, despite that fearful punishment,

she continued, though now fitfully, to fire.

It was not a pretty sight.

Bismarck was a menace that had to be destroyed, a dragon

that would have severed the arteries that kept Britain alive.

And yet to see her now, this beautiful ship, surrounded by

enemies on all sides, hopelessly outgunned and out maneuvered,

being slowly battered to a wreck, filled one with awe and pity...

By 10 a.m. the last of Bismarck's guns had fallen silent....

And then, as we looked at this silent, dead-weight shambles of a ship,

we saw for the first time what had previously existed only in our imagination,

the enemy in person, a little trickle of men in ones and twos,

running or hobbling towards the quarterdeck to escape from

the inferno that was raging forward; and as we watched

they began to jump into the sea.

By Ludovic Kennedy, from On My Way to the Club, pages 155 - 156

Passages: Writers on World War II (Part 2) will soon follow.