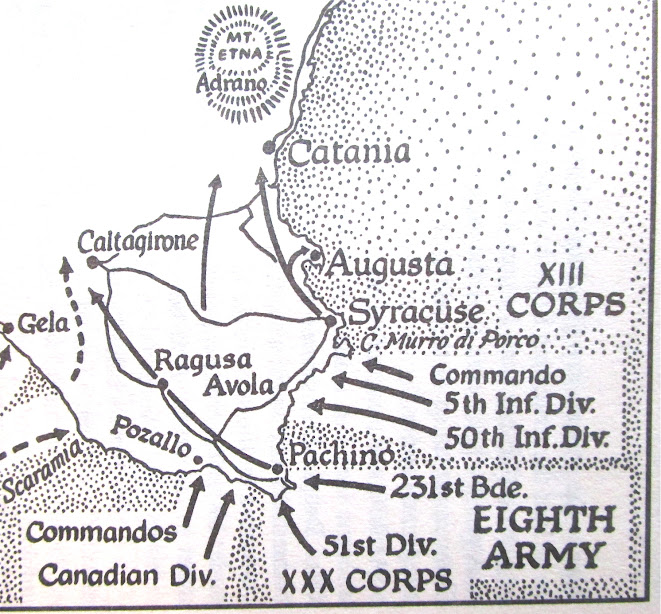

The Invasion of Sicily (Operation Husky), Begins July 10, 1943

Canadians in Combined Ops are Busy Beavers for 30 Days

Some Canadian ships travelled by way of the Mediterranean Sea

Photo found in Combined Operations, Clayton Marks, Pg. 77

The SS Silver Walnut went the long-way-round, i.e., around Africa.

Click here to read "Sicily, The Long Way 'Round" by D. Harrison

Introduction:

This present series shares stories and many photographs that can be found in Combined Operations, by Londoner Clayton Marks. As well, I share other related photographs, materials, links, etc. in order to tell as full a story as possible about the experiences of 950 - 1,000 Canadians sailors (members of RCNVR and volunteers for Combined Operations) during WWII.

Clayton Marks writes a significant history re these men and includes many unique stories from others he connected with over the years. His book was self-published in the early 1990s and reprinted just a few years ago. Connect w the editor of this site if interested in details about the book: gordh7700@gmail.com

Below are details concerning the invasion of Sicily, beginning July 10, 1943. The first photo relates to the top photo in this entry:

in operations in The Med. Photo H.M.C.S. by Gilbert A. Milne, pg. 108

Photo credit - As found at wikipedia

The photo was clipped from the Canadian National Magazine, July, 1944

As found in Combined Operations, page 78

The next three photographs are from the same page (as above) in Clayton Marks' book and I suspect they are from the same magazine (with same fonts, photographer):

This next photo appeared with the four others on page 78, but I found the original. It does not relate to the invasion of Sicily specifically, but is another look at Prince David, in action later in the war.

Photo Caption and Credit (those supplied to Clayton may be incorrect) - LCA

1050 (sic) leaving side of HMCS Prince David, loaded with soldiers of the

Régiment de la Chaudière, 9 May 1944. Photo by R. G. Arless.

Dept. of National Defence / Archives of Canada, PA-141525.

One last photo of HMCS Prince David at work, liberating "enemy soldiers!"

H.M.C.S.: One Photographer's Impressions..., by Lt. G. A. Milne, pg. 124

The story by C. Marks related to the action involving Canadians in Combined Operations during Operation Husky - the invasion of Sicily - and partially shared in the previous post, continues below, beginning on page 81:

The second misfortune concerned the airborne troops.

Two operations were planned for the night before D-Day - a British glider-borne landing and an American parachute drop. In both, the aircraft became badly scattered, owing to the high winds already mentioned; and only a fraction of the troops - though actually enough to do the job - reached their objective. Unfortunately in the British sector about a dozen out of 134 gliders were released too soon, and were lost in the sea, with many casualties.

Found in St. Nazaire to Singapore, Vol. 1 (pg. 181), by David. J. Lewis

C. Marks' story continues:

Air routes had been carefully planned to ensure that the airborne troops did not have to fly over the convoys; but something went wrong with the promulgation of these orders, and in a reinforcing operation three nights later, there were several cases of our own transport aircraft being shot down by our own ships. Failure in aircraft recognition was one of the causes.

Midnight brought the steady thunder of transport planes, passing over to land parachute troops inland. Half an hour later the assault convoy which included Otranto and Strathnaver arrived at its position seven miles off the coast above Pachino. Rolling in the heavy swell, the landing ships stopped their engines. Troops loaded down with battle equipment came up from the holds and began to climb into the landing craft hanging at the davits, a full platoon to each craft.

Midnight brought the steady thunder of transport planes, passing over to land parachute troops inland. Half an hour later the assault convoy which included Otranto and Strathnaver arrived at its position seven miles off the coast above Pachino. Rolling in the heavy swell, the landing ships stopped their engines. Troops loaded down with battle equipment came up from the holds and began to climb into the landing craft hanging at the davits, a full platoon to each craft.

One by one, as the platoons settled into their places, the swaying assault craft were lowered forty feet to the water below. Motors began sputtering; the craft moved away from the ships and formed up for the run to shore. It had been planned to have Fairmile motor launches lead each Flotilla separately to the assault point; but as only one Fairmile arrived it was necessary for the 55th Flotilla to take station on the 51st which followed directly behind the launch.

At fifteen minutes past one the wavering columns of flat-bottomed craft set off for the beach seven miles away. The night was black and the sea was very rough. It was windy, wet and cold. The soldiers huddling against the gunwales became sea sick; buckets came freely into use.

At fifteen minutes past one the wavering columns of flat-bottomed craft set off for the beach seven miles away. The night was black and the sea was very rough. It was windy, wet and cold. The soldiers huddling against the gunwales became sea sick; buckets came freely into use.

C. Marks' story continues:

Even some of the Naval stokers, working throttles amid the fumes of their torrid little engine rooms, began to feel the effects. Seas washing over the side called for constant bailing. Coxswains and Officers, peering ahead through the darkness, found it difficult to pick out the landmarks which had been shown to them on the charts before the operation began. Navigation of the craft, always difficult, became trebly so in the rough weather, with the southerly set of the water off the coast increased by the force of the wind. A searchlight knifed out from land, swung toward the craft, and illuminated every man's face in a white glare. Then it swept on, apparently having revealed nothing to the watchers ashore.

As the flights came nearer in they were unable to locate their beaches. Estimating that they had drifted a bit too far to the south, they turned and ran northward, paralleling the coast. A red flare, apparently dropped by a plane, blazed up; and in its light the exact landing place for the first wave of the Flotilla was revealed.

Abreast of each other the craft moved in. As they felt the scrape of sand along their bottoms, the ramps at the front went down and the troops stepped ashore, wet and miserable, crouching in anticipation of a blaze of fire. Only silence greeted them and they fanned out and made for their objectives. The empty landing craft began to withdraw, and it was not until they were again moving seaward that a single machine gun opened up to spatter the water about them.

The second wave of landing craft found their sector of beach protected by a breakwater which they had to skirt under light fire. As they rounded the breakwater and turned in to shore the fire grew a little heavier, but they grounded without casualties on the rocky beach. The ramps went down, the bark of orders began amid the whistle and spatter of machine gun bullets, and wet, whey-faced, seasick soldiers, bending under their heavy battle gear, stumbling along decks slimy with sea water, fuel oil and their own vomit, set off unheroically on a historic campaign. Sailors, equally wet, half as miserable, and certainly not envying their "pongo" brothers*, made haste to get their craft back to the older element.

C. Marks' story continues:

Another wave of assault landing craft was standing off shore with parties of engineers whose work would be to clear mines when the beaches were secured. Some fire from machine guns and howitzers was falling unpleasantly near, but the main sounds of battle were retreating inland. It seemed clear that the beaches had been gained with little resistance, and the engineers and the landing craft men began to watch impatiently for the Verey light signals from shore which would call them in. The defenders were making things difficult by setting off their own flares of every colour, but at last the authentic signal came and the craft raced in to beach.

Section of the map from Combined Operations, page 76

Dad was a member of the 80th 'CDN LCM Flotilla.' GH

Fire from shore grew sharper and was unpleasantly accurate, but once again no casualties resulted. By four-thirty in the morning, all the assault landings had been made. The beaches were securely held; mine clearing was in progress. It remained only to ferry the reinforcement troops ashore and empty the transports so that they could move away from the beaches before enemy aircraft arrived.

Sunrise came at three minutes before six, and promptly at six a JU88 put in an appearance. A little later two Messerschmitts swept down to strafe the ships with cannon fire.

Following the assault convoys and moving into station off the beaches even before the first arrivals withdrew, came ships with the heavier mechanized equipment and supplies for depots to be established inland. Vessels carrying the larger landing craft came with them, and two of these carried the 80th and 81st Canadian LCM Flotillas which were to land near Avola*. The LCM's began their work four hours after the LCA's but instead of finishing in twelve hours, they were to be occupied for some ten weeks, first on Sicily and then on the Italian mainland.

Used w permission of Joe Spencer, RCNVR, Comb. Ops

[*The editor's father, Doug Harrison, provides a detailed account of landing near Avola as part of the 80th LCM Flotilla, and settling into a cave as the transport of goods continued for about 4 weeks. Next came recuperation from dysentery and the repair of LCMs at Malta, followed by the invasion of Italy.]

The following four photos from St. Nazaire to Singapore, Volume 1 relate to the invasion of Sicily:

The first of the LCM's were lowered from their parent ships at about five-thirty on the morning of the assault, a few minutes before sunrise. Loaded with vehicles and stores, they steered in toward beaches now securely held, deposited their freight, and turned back for more. For the first few hours there was no interruption to the ordered chaos of the build-up. Transports stood off the coast, each with its identification number placarded on its side. Landing craft ran in under their high sides, loaded with feverish haste and put off to unload at the same tempo ashore, satisfying the most urgent of the hand-to-mouth requirements.

At one point gasoline would be required to get vehicles moving inland; at another troops would be running short of ammunition. Headquarters units would require more signalling equipment; troops held up by resistance on the forward fringes might need a howitzer to break through. The landing craft was diverted from ship to ship and from point to point along the beaches to meet each need as it developed. This was the preliminary phase of the work, preceding the stage when shore depots would be established and stored; and it had to be got over with in a hurry before enemy aircraft arrived.

The following four photos from St. Nazaire to Singapore, Volume 1 relate to the invasion of Sicily:

C. Marks' story continues:

The first of the LCM's were lowered from their parent ships at about five-thirty on the morning of the assault, a few minutes before sunrise. Loaded with vehicles and stores, they steered in toward beaches now securely held, deposited their freight, and turned back for more. For the first few hours there was no interruption to the ordered chaos of the build-up. Transports stood off the coast, each with its identification number placarded on its side. Landing craft ran in under their high sides, loaded with feverish haste and put off to unload at the same tempo ashore, satisfying the most urgent of the hand-to-mouth requirements.

At one point gasoline would be required to get vehicles moving inland; at another troops would be running short of ammunition. Headquarters units would require more signalling equipment; troops held up by resistance on the forward fringes might need a howitzer to break through. The landing craft was diverted from ship to ship and from point to point along the beaches to meet each need as it developed. This was the preliminary phase of the work, preceding the stage when shore depots would be established and stored; and it had to be got over with in a hurry before enemy aircraft arrived.

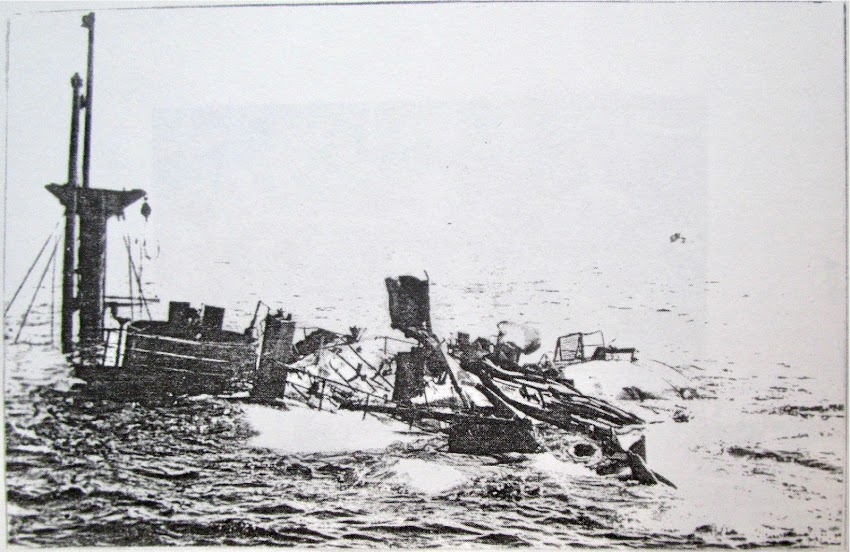

The comparative quiet was broken at nine o'clock in the morning. An enemy bomber came in very fast and dropped a stick of bombs along a stretch of shoreline occupied by two British vessels and by the Canadian landing craft carrying the Senior Officer of the 80th Flotilla. The smaller British vessel, a tank landing craft, was squarely hit and blown to pieces.* The other British ship was heavily damaged, and every man on her bridge was killed. The Canadian craft, well up on the beach with some of her men ashore nearby, had a miraculous escape. The force of the explosions knocked down the men on the beach, and the Flotilla Officer was blown back into the well deck of his ship, but no one was injured. Considerably-dazed, but marveling at their luck, the men recovered and went to the assistance of the British merchantman, helping to take off her wounded and transfer them to a hospital ship.

[*My father, a member of the 80th Flotilla, describes his experiences re the bombings in his navy memoirs.]

My father saw his first Landing Craft Infantry, Large (LCI (L))

during Operation Torch, invasion of Sicily, July 1943

The decline of the Luftwaffe's efforts was rapid, however. Air cover from Malta began to show its murderous effectiveness, and by the third day planes flying from captured Sicilian bases were adding their strength to the Allied umbrella.

During the four weeks that followed, the work of landing stores and reinforcements settled down into a routine for the craft of the 80th and 81st Flotillas. It was a grinding routine, and it was never free from danger. Every type of cargo had to come ashore in their craft; sixteen-ton tanks, heavy trucks, tiers of cans of high-octane gasoline, ammunition, army rations, small arms and mortars. Heavy seas often made both the run-ins and the work of loading and unloading very difficult. The huge requirements of the armies put heavy pressure on the ferry system and for the first forty-eight hours of the operation every man remained on the job without rest. Even after that, the best arrangement that could be worked out was a routine of forty-eight hours on for twenty-four hours off....

During the four weeks that followed, the work of landing stores and reinforcements settled down into a routine for the craft of the 80th and 81st Flotillas. It was a grinding routine, and it was never free from danger. Every type of cargo had to come ashore in their craft; sixteen-ton tanks, heavy trucks, tiers of cans of high-octane gasoline, ammunition, army rations, small arms and mortars. Heavy seas often made both the run-ins and the work of loading and unloading very difficult. The huge requirements of the armies put heavy pressure on the ferry system and for the first forty-eight hours of the operation every man remained on the job without rest. Even after that, the best arrangement that could be worked out was a routine of forty-eight hours on for twenty-four hours off....

The conclusion of C. Marks' account will follow in the next entry of this series.

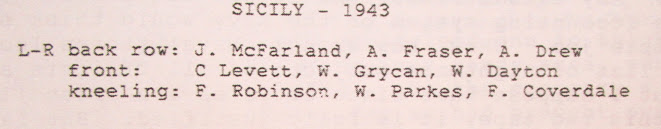

This particular entry will conclude with the following three photos from Combined Operations by Londoner Clayton Marks, pages 88 - 89:

This particular entry will conclude with the following three photos from Combined Operations by Londoner Clayton Marks, pages 88 - 89:

For more information about the same topic, please link to Photographs: Canadians in "Combined Operations" (Part 5)

More to follow.

Unattributed Photos GH

No comments:

Post a Comment