Excellent Story by Canada's Scott Young.

(Still No Sholto Watt!)

Headlines and top articles in The Montreal Daily Star

I am aware that Scott Young (father of singer/song-writer Neil Young) accompanied Canadian forces as a war correspondent during actions in the Mediterranean Sea. Readers can find interesting pieces he submitted to Canadian newspapers in the collection of news stories I have already posted re Sicily (links re Sicily are available in 'click on Headings' in the side margin). The stories were found in The Winnipeg Tribune, a digitized paper, archived at the University of Manitoba, well worth checking out.

I was not aware that articles by Sholto Watt would be so rare or hard to find in The Montreal Star. I am starting to wonder if he grew ill or was injured after he had submitted his first story, posted earlier here. I will keep scanning microfilm - hopefully to find Sholto - until I reach into early October.

That being said, more September stories can still be easily found to inform us of the varied degrees of progress made by Allied troops against stubborn German defensive forces on the Italian peninsula in the fall of 1943.

While Canadians in Combined Ops (including my father) continued to toil in Reggio di Calabria, ferrying supplies from Messina (Sicily) needed by advancing troops that had landed on the toe of Italy's boot on Sept. 3rd, descriptions of rough landings and actions around beachheads near Salerno and Naples are being filed by many war correspondents. Just not Sholto Watt.

News from The Montreal Star:

Some Italian prisoners do not look too disappointed to see the end of their war. And many of the men were soon put to work helping to unload landing crafts. They were paid with food and cigarettes.

Italy's navy fell into Allied hands, and regrouped (in part) in Malta and Taranto (near the heel of the boot). Meanwhile, Allied forces had a savage time holding onto their beachheads near Salerno and Naples:

From right to left, one can see the three arrows below that point to Taranto (heel), Reggio (easy Allied landings on the toe), and Salerno and Naples. The slow, difficult march north toward Rome lasted until June, 1944.

British Commandos and US Rangers trained in much the same ways and were often given the most desperate assignments. Many units trained in northern Scotland, as did Canadians in Combined Ops:

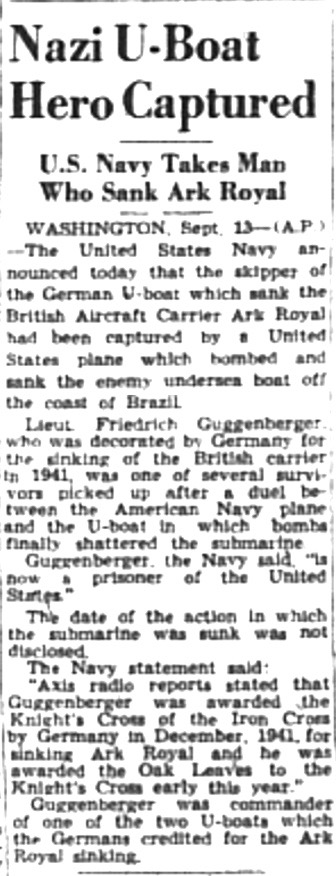

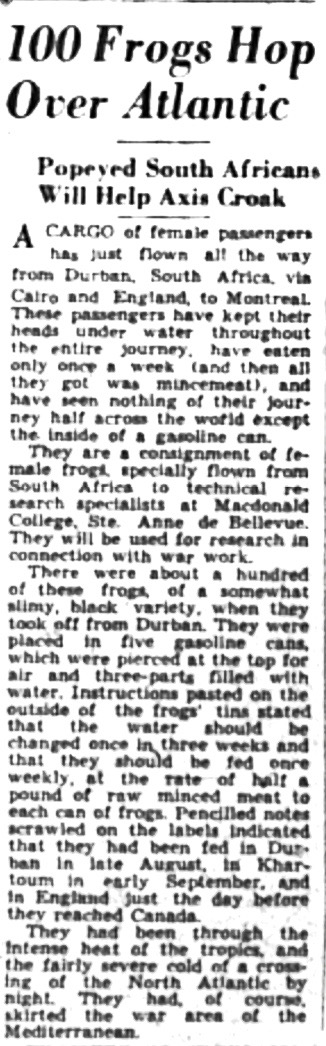

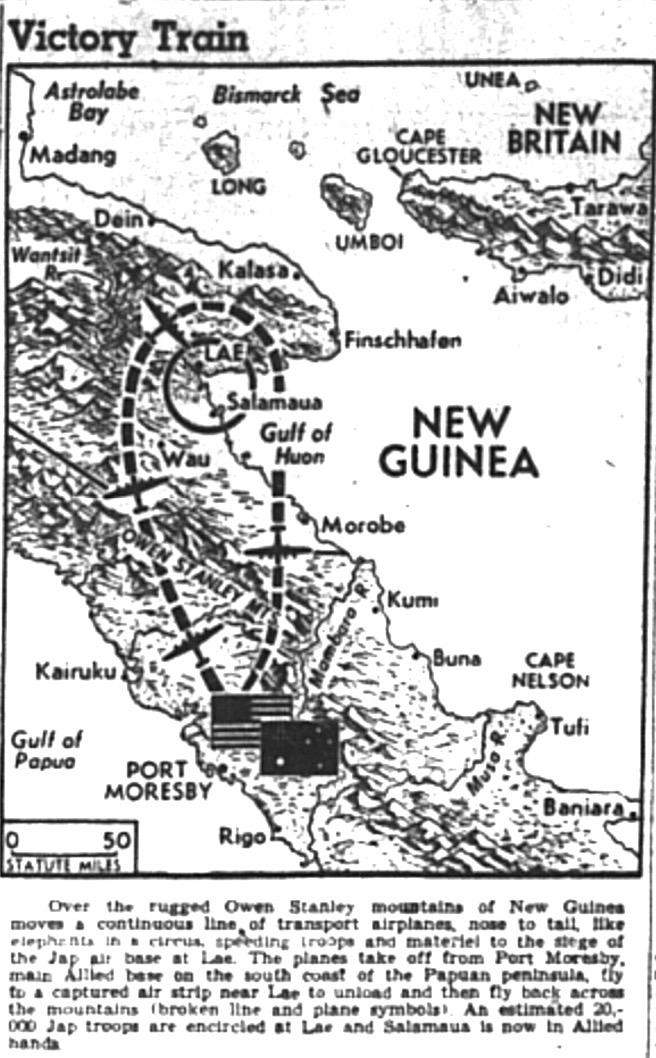

War stories are coming from all fronts - re U-Boats in Brazil, the RAF in the Mediterranean, and four-legged creatures on the Atlantic - even a kitchen in the UK!

Germany is losing the battle in Russia, and Russia's momentum will eventually carry the Red Army all the way to Berlin:

The "Bright and Breezy" Montreal Herald might not get too far with this cartoon feature today:

War correspondent Scott Young lists several Canadian units which stood tall in Sicily and continued to roll into battle on the Italian mainland:

Related to the desperate action between Allied and German forces in the Salerno area, please find below an excerpt from Combined Operations by Londoner Clayton Marks (continued from Invasion of Italy (8):

Once again the use of smoke, as in the crossing of the Messina Straits, proved to be a mistake. The enemy gunners had ranged on the beaches, and their aim was not affected by their inability to see their targets; whereas the attackers could not see what was going on, and coxswains found difficulty in recognizing the silhouettes which they had so carefully memorized. During an air raid on the first evening, two cruisers, Delhi and Uganda, were actually in collision in a smoke screen.

Destroyers were steaming close inshore to engage shore targets, cutting across the bows of landing craft as they steered their painstaking way. The exits from the beaches were bad, and there was not room in the beachhead to deploy all the artillery that careful planning had got ashore in the early stages. The deficiency in fire support was made by units of the Royal and United States Navies. Every round fired from the sea during those fourteen hectic days in September of 1943 was a horrid warning to professors of tactics not to be dogmatic. A strong case could be made out in support of a claim that Naval bombardment saved Salerno. The lessons deriving from this experience were to be applied with devastating effect in Normandy nine months later.

On the extreme left of the British front, the American Rangers and British Commandos, were having a rough time. The LCA's which were to have landed the Commando stores apparently found the fire too heavy for their liking, and withdrew without unloading. Objectives changed hands more than once, but were finally captured and handed over to the left flank British division. Out of a total strength of 738, more than half ware casualties. As the landing craft came ashore, all supplies were unloaded and stored, and the beach area was kept clear for incoming craft by the Indian Gurkhas and Italian prisoners.

In the American areas, south of the Sele River, the battle remained critical for several days. For some reason fewer close support craft were allotted to this part of the front, and all landings were made under heavy machine gun fire. Here again, the exits from the beaches were defective and the build-up caused many delays. American reports on Salerno are sternly self-critical. The scales of equipment taken ashore were far too generous; no labour was provided to unload the LCT's and the DUKW's. DUKW's were misappropriated and used as trucks instead of returning to the ships for more stores.

Many ships had been improperly loaded, with a lot of irrelevant and unauthorised items on top of the urgently required tactical ones, and at one stage there was a mass of unsorted material - petrol, ammunition, food, equipment - lying so thick on the beaches that landing craft could find nowhere to touch down. Eventually a thousand sailors were landed from the ships to clear the waterfront, and pontoons were rushed in to the sector to make piers. But for some time all landing of stores had to be suspended.

Although some of the troops had penetrated inland a mile or more by first light on the 9th, they were very weak, and when the Germans counter-attacked with tanks they had nothing with which to defend themselves. The first American tanks did not get ashore until 10 a.m. From 0800 onwards, regardless of the risk of mines, two American cruisers, the British monitor Abercrombie, and several destroyers, both British and American, were engaging enemy tanks from seaward. The American destroyer Bristol fired 860 rounds during the day, closing at one time to a range of 7500 yards.

On the 11th, the Germans produced a new and nasty weapon, the remote controlled bomb. These were released by aircraft flying at a great height, and steered on to the targets by electronic means. The first two fell within six minutes of each other: No. 1 missed the U.S. cruiser Philadelphia by only fifteen feet, and shook her from truck to keel and No. 2 scored a direct hit on the Savannah and set her on fire.

H.M.S. Uganda was hit a few hours later and severely damaged, though both she and the Savannah survived. During the next few days several ships were victims of the formidable new weapon, including the battleship Warspite.

Some Italian prisoners do not look too disappointed to see the end of their war. And many of the men were soon put to work helping to unload landing crafts. They were paid with food and cigarettes.

Italy's navy fell into Allied hands, and regrouped (in part) in Malta and Taranto (near the heel of the boot). Meanwhile, Allied forces had a savage time holding onto their beachheads near Salerno and Naples:

From right to left, one can see the three arrows below that point to Taranto (heel), Reggio (easy Allied landings on the toe), and Salerno and Naples. The slow, difficult march north toward Rome lasted until June, 1944.

British Commandos and US Rangers trained in much the same ways and were often given the most desperate assignments. Many units trained in northern Scotland, as did Canadians in Combined Ops:

War stories are coming from all fronts - re U-Boats in Brazil, the RAF in the Mediterranean, and four-legged creatures on the Atlantic - even a kitchen in the UK!

Germany is losing the battle in Russia, and Russia's momentum will eventually carry the Red Army all the way to Berlin:

The "Bright and Breezy" Montreal Herald might not get too far with this cartoon feature today:

War correspondent Scott Young lists several Canadian units which stood tall in Sicily and continued to roll into battle on the Italian mainland:

Related to the desperate action between Allied and German forces in the Salerno area, please find below an excerpt from Combined Operations by Londoner Clayton Marks (continued from Invasion of Italy (8):

SALERNO - OPERATION AVALANCHE

Once again the use of smoke, as in the crossing of the Messina Straits, proved to be a mistake. The enemy gunners had ranged on the beaches, and their aim was not affected by their inability to see their targets; whereas the attackers could not see what was going on, and coxswains found difficulty in recognizing the silhouettes which they had so carefully memorized. During an air raid on the first evening, two cruisers, Delhi and Uganda, were actually in collision in a smoke screen.

Destroyers were steaming close inshore to engage shore targets, cutting across the bows of landing craft as they steered their painstaking way. The exits from the beaches were bad, and there was not room in the beachhead to deploy all the artillery that careful planning had got ashore in the early stages. The deficiency in fire support was made by units of the Royal and United States Navies. Every round fired from the sea during those fourteen hectic days in September of 1943 was a horrid warning to professors of tactics not to be dogmatic. A strong case could be made out in support of a claim that Naval bombardment saved Salerno. The lessons deriving from this experience were to be applied with devastating effect in Normandy nine months later.

On the extreme left of the British front, the American Rangers and British Commandos, were having a rough time. The LCA's which were to have landed the Commando stores apparently found the fire too heavy for their liking, and withdrew without unloading. Objectives changed hands more than once, but were finally captured and handed over to the left flank British division. Out of a total strength of 738, more than half ware casualties. As the landing craft came ashore, all supplies were unloaded and stored, and the beach area was kept clear for incoming craft by the Indian Gurkhas and Italian prisoners.

In the American areas, south of the Sele River, the battle remained critical for several days. For some reason fewer close support craft were allotted to this part of the front, and all landings were made under heavy machine gun fire. Here again, the exits from the beaches were defective and the build-up caused many delays. American reports on Salerno are sternly self-critical. The scales of equipment taken ashore were far too generous; no labour was provided to unload the LCT's and the DUKW's. DUKW's were misappropriated and used as trucks instead of returning to the ships for more stores.

Many ships had been improperly loaded, with a lot of irrelevant and unauthorised items on top of the urgently required tactical ones, and at one stage there was a mass of unsorted material - petrol, ammunition, food, equipment - lying so thick on the beaches that landing craft could find nowhere to touch down. Eventually a thousand sailors were landed from the ships to clear the waterfront, and pontoons were rushed in to the sector to make piers. But for some time all landing of stores had to be suspended.

Although some of the troops had penetrated inland a mile or more by first light on the 9th, they were very weak, and when the Germans counter-attacked with tanks they had nothing with which to defend themselves. The first American tanks did not get ashore until 10 a.m. From 0800 onwards, regardless of the risk of mines, two American cruisers, the British monitor Abercrombie, and several destroyers, both British and American, were engaging enemy tanks from seaward. The American destroyer Bristol fired 860 rounds during the day, closing at one time to a range of 7500 yards.

On the 11th, the Germans produced a new and nasty weapon, the remote controlled bomb. These were released by aircraft flying at a great height, and steered on to the targets by electronic means. The first two fell within six minutes of each other: No. 1 missed the U.S. cruiser Philadelphia by only fifteen feet, and shook her from truck to keel and No. 2 scored a direct hit on the Savannah and set her on fire.

H.M.S. Uganda was hit a few hours later and severely damaged, though both she and the Savannah survived. During the next few days several ships were victims of the formidable new weapon, including the battleship Warspite.

She had been shelling the shore batteries. She had just blown up an ammunition dump, and was moving contentedly to the north to shoot up another area, when three remote-controlled bombs came whistling down on her. Two were misses, but the third burst in one of her boiler rooms. In less than an hour her engine rooms were flooded and she was helpless. A hazardous tow of 300 miles brought her to Malta. It took five hours to get her through the Straits of Messina, due to the strong currents.

Pages 103 - 104.

The following cartoon may seem a bit optimistic after learning that German defensive measures were incredibly stiff during Allied attempts to form beachheads near Salerno and Naples.

A war orphan won the hearts of many a tough flier:

Monty speaks the truth: "The Germans must not be underestimated." He also said, "But the Canadians are with me now and they're first class - excellent."

The cover of the book is too dark to make out but it would certainly be a good one to search for in used-book shops. Ten cents isn't a bad deal!

Again, save up your nickels (15 of them will do) and go "Meet the Navy."

More stories to follow as I try to answer the question, "Where's Sholto?"

Please link to Invasion of Italy (9) - Montreal Star (Sept. 11, '43)

Unattributed Photos GH

Pages 103 - 104.

The following cartoon may seem a bit optimistic after learning that German defensive measures were incredibly stiff during Allied attempts to form beachheads near Salerno and Naples.

A war orphan won the hearts of many a tough flier:

Monty speaks the truth: "The Germans must not be underestimated." He also said, "But the Canadians are with me now and they're first class - excellent."

The cover of the book is too dark to make out but it would certainly be a good one to search for in used-book shops. Ten cents isn't a bad deal!

Again, save up your nickels (15 of them will do) and go "Meet the Navy."

Please link to Invasion of Italy (9) - Montreal Star (Sept. 11, '43)

Unattributed Photos GH

No comments:

Post a Comment