Details Related to an Upcoming Presentation

How Did 950 Canadian Sailors Get Into Combined Ops?

Canadians in Combined Ops were transporting Canadian troops and

all materials of war to the toe of the boot when Italy surrendered

*. *. *. *. *

After a lengthy introduction, the presentation continues with "early days in training, volunteering for Combined Operations."

1. From Hamilton to Halifax to Combined Operations

Dad, from Norwich ONT, 16 miles south of Woodstock, enlisted in the RCNVR, the Wavy Navy, at Hamilton Division 1, in the Steel City in summer, 1941.

Dad, from Norwich ONT, 16 miles south of Woodstock, enlisted in the RCNVR, the Wavy Navy, at Hamilton Division 1, in the Steel City in summer, 1941.

He writes:

Note: No, he didn't. The Navy base became known as HMCS Star on November 1, 1941 about 4 - 5 months after Dad enlisted. However, in his defence, he wrote his memoirs in the 1970s when Star was 30-years old. And he recalls the original location of Division 1 and that earlier it had produced cider.

By probationary I mean I went nights from 7 to 10 p.m. and took instructions on semaphore, rifle drill, marching, compass work, bends and hitches, knots and splices etc....

Other aspects of his training are listed as well:

* black garters? Help! Your combined knowledge is more than I'll ever have.

Comedy too was all part of naval life. We had to scrub and wax and polish the ward room floor, and after waxing we put a rating in a clean pair of overalls onto the floor and dragged him by his arms and ankles to polish it. Needless to say, corners were tough on his head.

You might ask, if you know where Dad's hometown of Norwich is, why would he enlist in Hamilton and not London, which is closer.

I think I have the answer:

I lived with my late sister Gertrude (also an older sister) on Bay St., Hamilton. During the day I was employed at James St. North Hamilton Cotton Mills where I progressed from one job to another very rapidly.

So, Dad likely found it easier to live in Hamilton, not too far north of the navy base, where he could work at a nearby cotton mill to help pay room and board. And some of his details about that reveal a bit about his view of those in authority, resulting in one of the best run-on sentences I've ever run across:

A former cotton factory became a creative hub in Hamilton

When eight weeks of training were over we were shipped to Halifax, but not before the 80 of us, led by our mascot (a huge Great Dane led by Scotty Wales who was under punishment) and headed by a band, did a route march through Hamilton in early evening. We really were proud and put on a display of marching never seen before or since in Hamilton.

Photo - marching in Hamilton

From Dad's collection, perhaps taken by his sister Gertie

Shoulders square, arms swinging shoulder high, thousands watched and we were roundly cheered and applauded. This was a proud moment long-remembered, but soon we were bound for Halifax after a goodbye to Mum and family. Again I say we were a proud division and our training was to stand us in good stead in Halifax. Because if Hamilton was tough, it couldn’t hold a candle to Halifax.

Dad mentioned a few details about the training:

Training was very severe in Halifax. Can you imagine running outside in temperatures in the low twenties in T-shirts and shorts? We did, morning after morning.

"At Nelson Barracks, Halifax... an enjoyable hour of rope climbing?" Sarcasm??

Photos from Sailor Remember by William Pugsley, RCNVR

Dad continues, related to the running:

O/D Seaman Ward of Niagara Falls was very heavy so he jumped on the street car and then met us at Stadacona’s gate and fell in at the rear. Never ran a step, still, no one ever squealed on him.

beside his friend Jim Cole. They appear together in another photo too.

Top row, on left... four of Dad's best mates - Joe, Chuck, Art, Joe

"Quebec, Ray and Jim 1942" from the collection of Joe Spencer, RCNVR.

Has Ray slimmed up a bit? Photos sent to me Gary Spencer, Brighton, ONT

More information re "HMS Quebec" (Scotland) in just a few minutes

Here's how the new recruits handled one particular tough situation in Halifax in late 1941:

We went six weeks before being allowed to go ashore and that also was ruined by a seaman known only as Thibodeau.

I was initially confused by what "go ashore" meant. Dad was at a Navy base, not on a ship - but I slowly learned that to leave the boundaries of Stadacona or any land establishment was considered "going ashore" as if from a ship.

The division was really angry (because) Thibodeau dropped a pint of milk out of a window nearly hitting the Officer of the day making his evening rounds to see if everything was clean. Our leave was cancelled indefinitely. We went to our Leading Seaman Instructor, L/Seaman Rose but he said he couldn’t help us, but we probably wouldn’t be seen if we ourselves took a course of action. Into the cold showers went O/D Thibodeau, clothes and all, as if the barracks weren’t cold enough for him already. He was on good behaviour from then on and we soon got permission for a few hours leave every other night.

** Thibodeau does not show up in any other stories or photos, even group shots

Here's the toughest situation my father recounts, toughest especially for me!

My girlfriend and my mother sent me a Rolex Oyster wrist watch for Christmas. I put it on and went to the washroom for a shave and wash, took off the watch, forgot it, and never saw it again. I probably had the watch for about half an hour. I told my mother I smashed it during rifle drill. “And it took us weeks to pay for it!!” said Ma.

** Thibodeau does not show up in any other stories or photos, even group shots

Here's the toughest situation my father recounts, toughest especially for me!

My girlfriend and my mother sent me a Rolex Oyster wrist watch for Christmas. I put it on and went to the washroom for a shave and wash, took off the watch, forgot it, and never saw it again. I probably had the watch for about half an hour. I told my mother I smashed it during rifle drill. “And it took us weeks to pay for it!!” said Ma.

I found a 1940s newspaper ad for the Rolex Oyster watch, $69.95, a lot of money in those days. But when I watch Antiques Roadshow and hear about their value today... that's tough to bear.

More details/stories about the training of young recruits in Halifax comes from Lloyd Evans, also a member of RCNVR and Combined Operations during WWII:

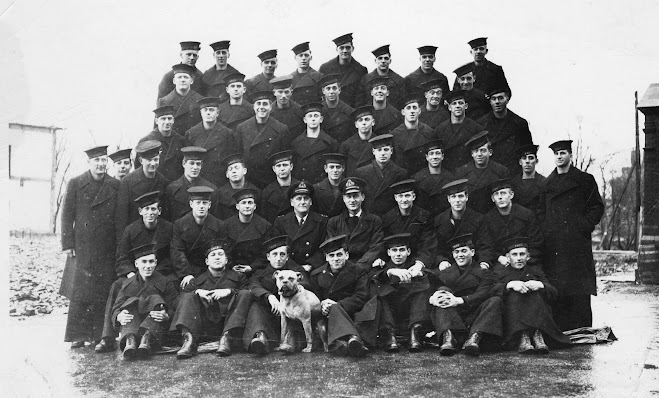

Lloyd, back row, part of the 2nd Canadian division to volunteer

for Combined Ops in late 1942. A few other faces are familiar too

Photo is from the Lloyd Evan's collection, given me by his son Steven.

The new entry training (in Halifax) was at the ex-army Wellington Barracks (then C Block of HMCS Stadacona). The training consisted of knots and splices, rifle drill, semaphore, Morse code, ship and aircraft recognition, gunnery drill and parade drill.

The highlight of the training was a one-day trip to sea on a Minesweeper for gunnery practice. The whole ship rattled and shook when the 4-inch gun went off. It wasn't all fun - one of our boys was so seasick he pleaded to be thrown over the side! I heard later that he was posted to sea and was just as sick and still pleading to be thrown overboard. He finally got his wish when his ship was hit by a torpedo!

Concerning Naval training in 1941, Hamilton was tough, Halifax was tougher but it would "stand many a young recruit in good stead", especially the 950 - 1,000 sailors (approx.) who were soon training overseas with, and like commandos, in far off corners of NW Scotland, amongst other locations in the United Kingdom, as members of Combined Operations.

Concerning Naval training in 1941, Hamilton was tough, Halifax was tougher but it would "stand many a young recruit in good stead", especially the 950 - 1,000 sailors (approx.) who were soon training overseas with, and like commandos, in far off corners of NW Scotland, amongst other locations in the United Kingdom, as members of Combined Operations.

So, how did Dad and his mates get into Combined Ops?

On page 7 in "Dad Well Done" my father writes:

One day (in Halifax, in November 1941) we heard a mess deck buzz or rumour that the navy was looking for volunteers for special duties overseas, with nine days leave thrown in. Many from the Effingham Division, including myself, once again volunteered. (Will I ever quit volunteering?) The buzz turned out to be true and we came home on leave, which involved three days coming home on a train, three days at home and three days on the train going back.

My father shared a bit more information in a newspaper column in the 1990s:

Effingham Division, the first group from Canada to volunteer for Combined Ops

Dad, front; Ray Ward, 2nd row. Then Richard Cavanaugh with WHITE X

We had come to know each other very well over a period of six months, and were swayed greatly by the fact that it seemed an excellent way to stay together. So, come what may, we volunteered for the unknown, almost to a man.

Lloyd Evans writes:

Pre-Dieppe, June 1942? Photo - Lloyd Evans.

Al Kirby, from Woodstock Ontario, later in life the president of the Woodstock Navy Club, wrote the following:About this time my father said:

After returning from leave we were put aboard a large passenger liner, Queen of Bermuda, which went aground going astern as we left harbour and couldn’t be moved.

I looked in copies of the Halifax Chronicle for any news item about the Queen of Bermuda, but found nothing except weather reports... re a nasty storm and lots of snow. However, I have since learned they crashed near Chebucto Head, which has been home to four lighthouses since 1872. The 2nd lighthouse was torn down in 1940 to make way for a gun battery. So it might have been dark out there the night the Bermuda ran aground.

night of the snow storm could be described as not normal

Dad added:

We bailed water all night with pails - and on a huge ship like that - it was like emptying a pail of sand one grain at a time. (Which is not normal!) However, we were transferred to a Dutch ship called the Volendam, (several days later) with a large number of Air Force men. This was to be an eventful trip.

And he was definitely right about that.

As found at Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21

Several sailors write about the trip because it was their first big trip aboard a passenger or cargo liner into very dangerous waters across the Atlantic Ocean.

I'll just list a few things my father recalls:

(We know, of course, the convoy consisted of many other ships carrying troops and supplies, but Dad recalls only those with arms, for protection of the convoy and the one lost protecting a convoy.)

The Dutch captain lined us all up and assured us we would arrive safely because the Volendam had already taken three torpedoes and lived to sail. This was very heartening news for those of us who had never been to sea except for a few hours in Halifax upon a mine-sweeper.

(Wait! "Heartening news?" "(?) I feel better now (?) after hearing about the torpedos that hit this ship I'm on?" I feel different about that... so maybe I'm not cut out to be in the Navy. "I'll stick to research!")

Dad remembers this:

Our first meal was sausage with lots of grease. Naturally, many were sick as it was very rough.

And:

And:

Late at night I was on watch at our stern and saw a red plume of an explosion on our starboard quarter. In the morning the American four-stacker was not to be seen. The next evening I heard cries for help, presumably from a life-raft or life-boat. Although I informed the officer of the watch, we were unable to stop and place ourselves in jeopardy as we only had the Firedrake with ASDIC (sonar) to get us through safely.

After some days we spotted a light on our port stern quarter one night. It was the light of the conning tower of a German submarine. How she failed to detect us, or the Firedrake detect it, I will never know. I was gun layer and nearly fell off the gun (4.7 gauge). I informed the Bridge and the Captain said, “Don’t shoot. Don’t shoot. It could be one of ours.” But as it quickly submerged we did fire one round to buck up our courage.

Some days later we spotted a friendly flying Sunderland and shortly after sailed up the Firth of Clyde to disembark at the Canadian barracks called Niobe. Before we disembarked, however, we took up a good - sized collection for the crew of the Firedrake for bringing us through.

**Pass Dad's hat!!

It was soon confirmed that the American four-stacker (mentioned earlier) had taken a fish (or a...torpedo).

Anything mentioned that might wake him up at night when he was in his fifties? The screams? The tin fish?

One item not mentioned is how many Canadian sailors in Combined Operations were aboard the Volendam.

99% of the Wavy Navy did what? Served on Destroyers, Minesweepers, Corvettes, Fairmiles... land establishments... coastal patrol... aboard navy planes... I don't know. I don't study that. I study the 1%, Canadians who - because they were still warm - volunteered for Combined Operations.

Anything mentioned that might wake him up at night when he was in his fifties? The screams? The tin fish?

One item not mentioned is how many Canadian sailors in Combined Operations were aboard the Volendam.

By The Numbers:

During WWII, about 100,000 Canadians enlisted in the RCN, most into the RCNVR (almost 95,000 or 95%, and listed in navy records as HO, Hostilities Only), and of that whole number (!) only 950 - 1,000 went into Combined Ops. That’s just 1%. And of that 1,000, about 100 left Canada aboard the Volendam after Christmas in 1941.

Photo - Navy records, HO, Hostilities Only

Because he volunteered for Comb. Ops a few oddities show up on dad's Navy records:

Another indication he was in C. Ops was a wee scribble - "C.O. - Tmpy"

Upon his return to Canada in Dec. 1943 and landing back at HMCS Stadacona he writes:

We met a lot of sailors, who were shortly to go through what we went through already (i.e., Dieppe Raid, invasions of North Africa, Sicily and Italy), and they called themselves commandos. They were sure in for a rude awakening. We were never called commandos, only combined operations ratings, or CO ratings, and we were the first from Canada to go overseas.

Now, "the first from Canada to go overseas" means "the first to go as RCNVR and CO volunteers." Their training, their role… seemed a big deal. Dad seems to be proud of his service here. “We were the first to go!” And though he says, "We were never called commandos," I've learned he and his mates trained with commandos, and trained like commando units. And Dad's division was in fact the first to do so in Canada.

And this is what I know. My father, part of the 1%, crewed landing crafts, LCAs (landing craft assault, troop transport mainly, 36 men), LCMs (men and all materials of war that would fit on it, e.g., ammunition, food, fuel, e.g., Jerry cans, and small vehicles, small guns on wheels, lorries - some already loaded with supplies, more food, more fuel, machinery parts, Navy rum* with an astericks....

and when he and his mates arrived in the U.K., e.g., Greenock, Scotland they did not have one clue about anything that was to come.

Last photo of part 2:

Greenock Central (Train) Station, Glasgow. Chuck Rose 1942

Used with permission, from Joe Spencer's collection

1%. That’s rubbed off on me. Small numbers = Rare. Hardly enough to make waves!! But, they had front row seats to raids, invasions, from St. Nazaire and Dieppe and North Africa (TORCH) in 1942; to invasions of Sicily (HUSKY) and Italy (BAYTOWN and AVALANCHE) in 1943.

Later groups of Canadians took part at Normandy (NEPTUNE and OVERLORD) in 1944. A handful trained others in combined operations on Vancouver Island in 1944 - 45. Doubly rare.

More to follow.

Unattributed Photos GH

%20(1922-1952)%20DI2013.594.1.jpeg)

No comments:

Post a Comment