Buryl McIntyre, RCNVR/Combined Operations, Norwich, Ontario

NORWICH BOYS IN THICK OF TWO INVASIONS BY ALLIES

LS. BURYL MCINTYRE AND LS. DOUGLAS HARRISON

WITH “BIGGEST ARMADA OF ALL TIME”

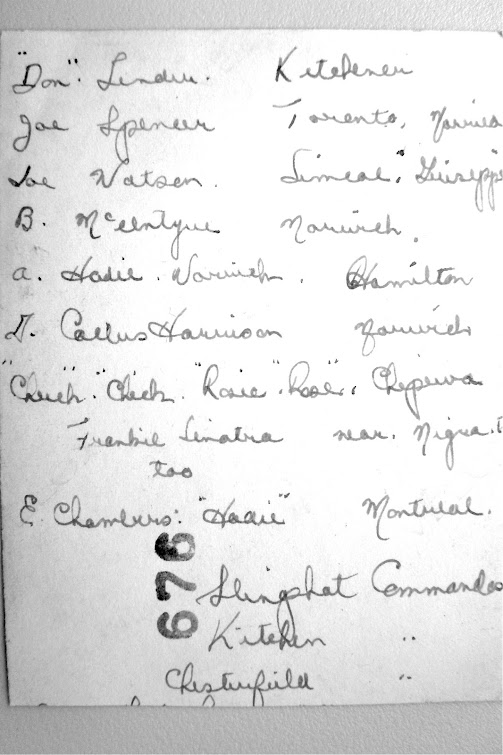

“I saw my lieutenant, the flotilla officer, ‘get it’ because he did not know the meaning of fear. I saw ship’s gunners being strafed and standing to their guns. I can remember a Bren gunner standing in plain view of wicked cross fire, pouring all he had into the Jerries to cover his mates’ landing.” LS. (Leading Seaman) Buryl McIntyre (on the left in photo below), home on leave in Norwich with his friend LS. Douglas Harrison (on the right) told what he remembered of Dieppe where he was mentioned in dispatches for his work as coxswain of a landing barge.

Buryl McIntyre and Doug Harrison (RCNVR, C. Ops.) Norwich, Ont.

From the collection of Doug Harrison (deceased), circa 1944-45

“It was a dark night in August when we crossed the Channel toward Dieppe. Just at dawn we could discern the coast of France. Out of the dark sky and into the light outlining the coast came a plane diving on gun positions on shore, the guns in his wings and cannon in the nose twinkling much like a ‘Hallowe’en sparkler’. Then as he was just below treetop height, so it seemed, he pulled out and let his bombs go. He zoomed up and set off for home, ‘a job well done’.”

Buryl’s lieutenant was shot down just as they were touching the beach and coxswain Buryl took command of the barge. After landing the troops, he pushed away to find the nearest destroyer to get help for his officer. He picked his way through the maze of boats, all moving as quickly as they could to avoid the bombing and strafing of enemy planes. Another barge drew alongside and tied up to see if there was anything they could do. As it pulled away its tie rope became entangled in the propellor of Buryl’s barge, stopping the engine. Buryl dropped into the water, swam around to the stern of the tossing barge and slowly unwound the rope. Then they pushed on.

Original caption w above photo*: “Soldiers pour out of landing barges. Note

ladders used to help scale obstacles” (Feb. 5, 1944, The Free Press)

Details from the Free Press interview continue:

He finally got his officer aboard a destroyer and stood by nine hours, waiting and watching. Finally a senior officer commanded him to take his barge home to an English port seventy miles across the Channel from Dieppe.

When the Dieppe honours were released Buryl McIntyre was mentioned in dispatches for coolness and courage in emergencies. Later he helped land the British First Army and supplies near Algiers and took part in the Allied landing in Sicily. During the invasion of Italy he was in a North African hospital.

LS. Douglas Harrison served in the invasion of North Africa, Sicily and Italy.

Both boys arrived in England in January 1942, and were attached to the Combined Operations of the Royal Navy for special training on invasion barges. For five months they underwent the stiff and constant training of combined operations, practising day and night landing manoeuvres with British and Canadian soldiers on the lochs of Scotland. Early in 1942, while still training, they had their first brush with the enemy. Coming down from Scotland in a convoy of carriers and barges, about eleven o’clock one night, they were attacked by ten Junkers 88s. One bomb struck the water and exploded just ahead of the boat they were on, splintering part of the ship and spraying the deck with shrapnel. The ship started to list badly but managed to right itself and there were no casualties.

After Dieppe, his seven day leave cut down to two, Buryl was almost immediately training for the next phase of the war. Late in October he and this time Douglas Harrison were in a great convoy bound for an unknown destination. Composed of all kinds of ships the convoy was loaded with machinery, bull-dozers, wire for landing sleds, jeeps, guns and the thousand other things which make up an invasion. They passed Gibraltar and proceeded along the North African shore. They saw and heard the silencing of shore batteries and presently were ready to land. Buryl handled a landing craft for the British First Army and Douglas worked with the Americans.

For three days they worked back and forth with their cargos until the port was taken and the ships moved in. Then they enjoyed the sunshine, the fruit and the French managing to avoid the Arab snipers. They bought German films, trinkets, souvenirs and marveled at oranges selling at less than thirty dollars a ton. Barges reloaded on their carriers, they returned to Scotland for more intensive training. When not in action men of combined operations spend their time perfecting styles of landing and setting up beachheads.

Early in 1943 they left England again, from different ports, on different dates, but both on the same mission - Sicily. After touching Cape Town and Durban, they met in Suez where they saw mainly sand. Then through the Suez Canal, into the Great Bitter Lake, called “second saltiest in the world,” the ships were gathered and furnished for the invasion. The Norwich seamen spent lazy nights in Egypt until the time to strike arrived.

Douglas had left his ship in Suez and had come by truck to the rendezvous. They began their journey west, on a varied course to mislead the enemy and dodge their bombs. On the night of July 10 they converged on Sicily, “the biggest armada of all time.”

Buryl’s carrier was a mile and half from the coast while Douglas’s was seven miles out. They began shuttling back and forth from ship to shore through the enemy barrage of shore batteries and bombs. They saw shore batteries being knocked out and German planes machine-gunning where traffic was thickest. Because Allied bombers had destroyed Sicilian airfields, German planes did not arrive in force for about six hours.

Until the Allies took over and prepared the Sicilian fields their fighters could not reach the invasion forces to protect them, so the landing was made under withering air attack. For four days the boys carried supplies through the thick of it, “but a barge makes a small target.”

After the fall of Sicily the boys landed and set up house-keeping. They were then able to get fresh fruit such as grapes, lemons and limes as well as fresh tomatoes. There was plenty of firewood and they did their cooking in biscuit tins. Aboard the barges they had used these tins as stoves, partially filling them with sand or cotton waste, pouring gasoline, sometimes mixed with oil, punching holes in the sides of the can around the top to provide air while cooking and stirring well before lighting. Such a fire would burn for a long time and could be given new life by adding a little fuel and stirring. They had been given rations aboard the barges but had to do their own cooking and make their own tea. On shore they swung their hammocks between the trees and since there were not enough nets to go around, treated themselves with anti-mosquito ointment. While camping here they met LAC Bill Donnelly, also of Norwich, an air-frame mechanic of fighting planes. He had been with the Eighth Army in Egypt, through Tripoli and Tunis and then in Sicily. He is now in Italy. He slept nights in an almond grove, his mosquito netting suspended from the lower branches of the trees.

Another Norwich boy, Reg Cole, with them in that convoy, was later killed in action in Italy.

Buryl was invalided from Sicily to a hospital base in Africa. Douglas went on to help the Canadians, the first invaders, land in Italy. Buryl was moved by ship from his hospital in Tripoli up the coast to Bone and from there by train to Algiers. There he met Douglas and they took the same ship back to Scotland. After 14 days’ leave in Scotland they started for Canada, arriving in December. When they leave Norwich they expect to go to the west coast.

They both maintain firmly that “the experience gained in the Dieppe invasion has saved thousands of lives in other larger-scale invasions.”

We were issued brooms for guard duty in some cases at Northney, sometimes a rifle with no ammunition, and they were expecting a German invasion. Rounds were made every night outside by officers to see if we were alert and we would holler like Hell, “Who goes there? Advance and be recognized.” When you hollered loud enough you woke everyone in camp, so sentry duty was not so lonesome for a few minutes.

There was no training here (at Northney), so, as the navy goes, we went back to Niobe on March 21, 1942. I recall just now we were welcomed to Niobe by Lord Hee Haw (a turncoat) from Germany via the wireless radio.

Thence to H.M.S. Quebec barracks in Ayrshire, Scotland on Loch Fyne. We were all in good shape and this was to be one of the more memorable camps, with our first actual work and introduction to landing barges. We trained on ALCs (assault landing crafts) which carried approximately 37 soldiers and a crew of four, i.e., Coxswain, two seamen and stoker. Some carried an officer.

O/D ‘Gash’ Bailey, called 'Gash' because he wanted everyone’s left-overs, aka ‘gash’ in Scotland (pudding is called duff), got in trouble over something (likely at HMS Quebec) and we, all drunked up, went to get him out of cells. A little army Sgt. Major said, “Call out the guard.”

Now, in the navy you are divided into two watches or groups, Port and Starboard, and one is on duty one night and free the next. On this occasion of uprising, the watch was used as the guard, and they got a key to the armory, got rifles and fixed bayonets. We Canadians were all lined up on the road facing the little Sgt. Major when he shouted, “Fix bayonets,” and then, “Load rifles.” O/D Buryl McIntyre, now passed away, had to show the guard how to load their rifles.

The Sgt. Major said, “You Canadians, right turn, and go back to your barracks.” We didn’t move. We next heard, “Guards, put your bayonets to their bellies. Canadians, quick march.” And we did. And there was no more fuss that night.

“I have no mess fanny or spoon,” I said, and the cook told me there were some fellows washing theirs up and to ask one of them for the loan of their mess fanny and spoon.

Naval tradition prevailed aboard the ship and at 11 o’clock each morning we were given a tot of navy rum which we didn’t have to drink under the watchful eye of some Chief Petty Officer. Buryl McIntyre and I were partners at bridge; we received good cards and placed second in the tournament; there being no main prize it was agreed that whichever team won the rubber of bridge also won their opponents’ tot of rum. Buryl and I slept quite well most nights, but with one eye open and one arm through our Mae West life jackets. Each ship has its own peculiar quirks and sounds; it is the unusual sound that brings sailors awake.

Buryl McIntyre and I were among the 200 sailors who had worked on our landing craft ferrying army supplies ashore night and day for about a week at a little town south of Oran named Arzew.

During the invasion, the Reina Del had acted as a hospital ship which we Canadian sailors could go aboard when tired. We were given excellent food, excellent rum, help to tumble into a hammock where we remained horizontal for many hours. The Reina Del served as a passenger liner again for many years after the war but unfortunately burned about 1970.

The Norwich Gazette column continues:

As my turn came to jump aboard the gang-plank, my eye spotted a large unexploded shell imbedded in the side of the ship not far from the officer’s head. I was very tired but not that tired, and inquired of the officer about the unexploded shell and he replied that the Captain had the shell examined and it was a dud. “I sure hope he is right because my mother will miss me, Mr. Wedd,” I said.

Mr. Wedd was dog-tired too and in no mood for an argument. “Your mother will miss you a lot more if you’re not aboard on the next swell, Harrison, because we are leaving. Do you hear me?” He added a bit more which couldn’t be printed and his ultimatum enabled me to time the swell of the next wave perfectly and I jumped to the gang-planks, and though tired, I found new energy at the cargo door and was soon amidships. The shell never exploded but it was sand-bagged and roped off.

It wasn’t long before the clank of the anchor cable could be heard in the hawse pipe. The anchors stowed, the gang-plank came on board and we were underway and in a few hours steaming at 27 knots (about 33 mph) we were safely inside the submarine nets at Gibraltar. In those few hours we organized bridge and crib tournaments.

The scene at Gibraltar was one of carnage, war at its worst. Nearby were destroyers which had been mauled by bomb and torpedoes, with gaping holes in their sides and deck plating, and some of the large guns were bent and pointed at bizarre angles. Miraculously they floated with pride and here and there steam came from the odd funnel. We thought of what the crews had been through and the fire and heat that had buckled the plates, how anyone could have survived. But Malta had to be fed.

Aboard the Reina Del at Gibraltar the Captain advised us to sleep up top under cover at night... (two paragraphs will not be fully repeated) ...Buryl and I slept quite well most nights, but with one eye open and one arm through our Mae West life jackets...

The Captain wished to miss the Bay of Biscay and as we skirted the western edge heading north we ran into a severe electrical storm. Standing well inboard under cover we witnessed the worst electrical display of our lives. Also, it seemed to rain so hard it pounded the sea flat. The ship retained good speed throughout and reached Liverpool safely in about four days.

Liverpool, such a friendly city, has welcomed sailors for centuries and we went ashore soon after our arrival to a seaman’s home, a large, warm, clean barrack-like building with good food, showers, and cots with white sheets and pillow cases. Heaven! Soon mail arrived and I can still see myself and my friends discarding our boots and stretching out on the cots to read the latest from home. Everything went quiet until someone shouted, “Hey guys, get a load of this!”

“Pipe down!” The old familiar phrase. “Read it to us later!”

We shared our parcels with anyone who may have missed out and showed new photos all around. Although we had shore leave, many chose to stay where we were, get some rest, and write some letters home. We did not see the Reina Del Pacifico again. One evening she slipped quietly away, but I for one have never forgotten her, our home for a few short days.

Pages 89 - 91

Buryl and Doug and four other Canadians in Combined Ops highlighted in this six-part series are just a few of the Canadian armed forces personnel who were able to tell a bit of their story as it related to World War II experiences once they returned home from Europe. Many quickly went back to work, as did my father, raised families and did not speak much about the war to their spouses or children. Many were never encouraged to share a story or write things down or get out their small, rare collection of black and whites. And many others simply did not survive to tell a tale.

No comments:

Post a Comment