The Invasion of the Toe of Italy's Boot, Beginning Sept. 3, 1943

Articles, Context from The Winnipeg Tribune, Sept. 11, 1943

Navies (Italian and Canadian), Nazis (Tanks Routed), and

the Conclusion of Baytown and Cashing Out in Paytown

Though I end this research project here, readers can slog through more

digitized stories by connecting to The Winnipeg Tribune at U. of Man

Introduction:

Allies win a "Prize" as the headline declares but at the same time their Armies must plough forward for many months to come. That being said, some members of Combined Operations are thinking about heading home to the UK. Some may even be thinking about what happens next, because their first two years in Combined Operations is almost up, and something new might be just around the corner.

Would the members of the 80th Flotilla of (Canadian) Landing Crafts know that once back in the UK there would be a lovely payday and a chance to go on leave... back to Canada?? I bet they did not have a clue.

Details re payday and home... soon to follow. First, a few news clips from The Tribune:

"Stiff German resistance" hampered the Allied landings, the establishments of beachheads as well as quick forward progress in and around Salerno, as mentioned in the news article below. (And near the bottom of the post, the viewpoint of Canadians in Combined Ops is expressed about this time period):

The last sentence above, re "the Calabria area" (the toe of the boot), refers to Monty's 8th Army, and it is being supplied in good part by the industry of Canadians in Combined Ops who man the 80th Flotilla of Landing Crafts. Few pieces of military memorabilia denote the existence/presence of the 80th, but the next photo - of a Navy hammock displayed at HMCS Naden Navy Museum in Esquimalt, Vancouver Island, British Columbia - reveals a significant piece, once the property of W. N. Katana, a Russian stoker who worked with my father Doug Harrison during Operation Baytown:

Photo Credit - Staff at HMCS Naden Navy Museum, Esquimalt, B. C.

In the summer of 2012 I saw the hammock; it smelled like diesel fuel. GH

And now back the the news article re "Nazi Tanks Routed":

With liberty comes a different form of justice...

Allied armed forces continue to train for D-Day Normandy under the noses of "the heavily fortified French coast":

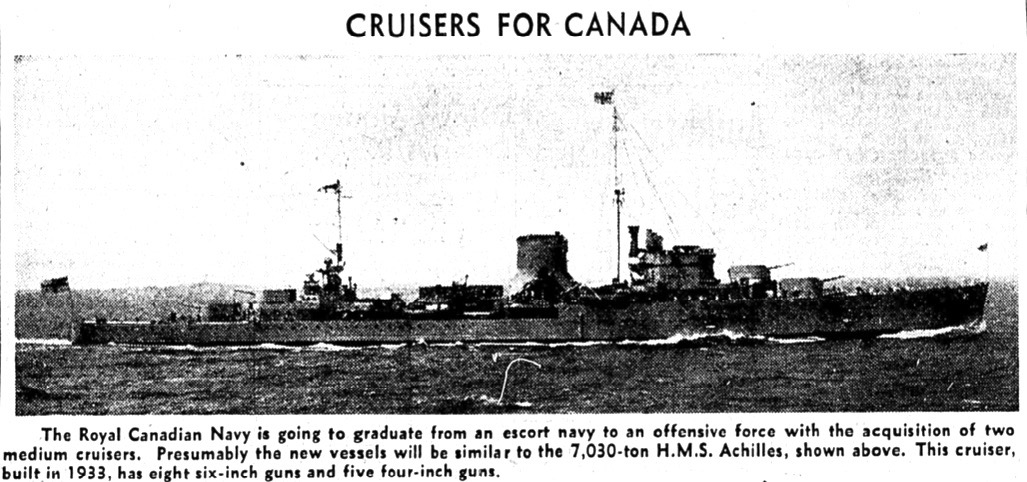

Canada's "Big Ship Navy" (as mentioned in an earlier news column by Torchy Anderson), grows even bigger:

The news clips from The Tribune come to an end with this short piece connected to a very big story, i.e., the "U-Boat war" or the "Battle of the Atlantic", a story so big* that all Canadians know something about it, for certain, even it's just a small bit:

[*'a story so big'. As many readers know, I chiefly focus on the work of 950 - 1,000 Canadians (approx.) who manned landing crafts from operations from Rutter (Dieppe, cancelled) and Jubilee (Dieppe, August 19, 1942) to Torch, Husky, Baytown, Avalanche (North Africa, Sicily, Italy respectively) and to Neptune and Overlord (D-Day Normandy) and even more. Occasionally I will go off on a tangent, follow another trail for a time, because when one gathers research material about one aspect re WWII there will be a lot of other material of interest seemingly caught or found in the same net. And so, there will soon be a post 11b in this series, inspired by a few items seen above re the navy hammock and the U-Boat war. And then the series will be done.]

Though Canadians in Combined Ops in charge of the 80th Flotilla of Landing Crafts continued to transport the materiel of war from Messina (and likely some other port cities in north eastern Sicily) to Reggio di Calabria for at least another two weeks before returning to England, I will conclude this research topic related to Operation Baytown very shortly. Pickings are growing very slim.

And though Canadians in Combined Ops connected to the 55th Flotilla of Landing Crafts may have continued to assist with efforts to supply US and UK troops at Salerno, near Naples re Operation Avalanche, I will conclude looking for more details about their efforts as well in The Winnipeg Tribune, as the war correspondents will be focussed almost exclusively on the tough slog ahead for Allied troops as they battle toward Rome and beyond.

In Combined Operations (stories by several RCNVR vets and members of Comb. Ops; written, collated and edited by Clayton Marks of London, Ontario) I find a suitable conclusion to both of the aforementioned operations.

About Operation Baytown we read the following:

Our next job was to act as ferry service across the Straits to keep a steady stream of vehicles and supplies to Monty's Men (i.e., as part of Operation Baytown beginning September 3, 1943). This was first done from Teressa (sic - Santa Teresa di Riva) and later from beaches north of the Messina harbour.

city and area. Preface by Editor of this site, 1,000 Men, 1,000 Stories, GH : )

In the latter place we were able to billet the Flotilla in houses close to the beaches. The various crews each had their own Italian boys to clean up after meals and tend to their dhobie. Pay for this service consisted of 'biscottis'. The work dragged on till once again the monotony of it got the better of nerves at times. Great was the rejoicing when on October 4th after disposing of our craft to Flotillas going to Naples and Taranto we were drafted to a small Combined Ops carrier for passage to North Africa.

During our month on the scene of this operation, not a single enemy plane was sighted, with the exception of one or two that got through to the landing beaches on the Italian side. Thus the Sicilian operation proved the most difficult of the two, just the reverse of our expectations. But then this war is a war of surprises isn't it!

In this account I have purposely neglected to mention numerous escapades into Italy. On their days off the Ratings - and Officers, I must confess - did go on the scrounge and sight-seeing.

During our month on the scene of this operation, not a single enemy plane was sighted, with the exception of one or two that got through to the landing beaches on the Italian side. Thus the Sicilian operation proved the most difficult of the two, just the reverse of our expectations. But then this war is a war of surprises isn't it!

In this account I have purposely neglected to mention numerous escapades into Italy. On their days off the Ratings - and Officers, I must confess - did go on the scrounge and sight-seeing.

The very tip of the toe of Italy is very similar to Sicily in many ways. Vineyards abound and the people were very friendly. There was one expedition I do remember, when our maintenance staff took a reporter from the Montreal Star* (bold italics mine - Editor) on a trip.

We landed at Scilla, looked over the town, including the local headquarters of the Fascista and came away with a tiny salute gun on the bow of our maintenance duty boat. We found the gun lying dejectedly on the slanting bridge deck of a partially sunken Messina-Reggio ferry boat. It was one of the many boats the Germans had used to escape across the Straits when they were pushed out of Sicily. It will be many a day before that regular ferry service is resumed, the boats are sunk and Messina itself is a shambles of the first order. Not a single building in the city proper is intact. Everywhere one sees the ravages that modern war metes out to any unfortunate city that lies in its path.

And so for the last time (or will it be the last time?) we saw the shores of Sicily recede in the distance, but we weren't looking back, our eyes and thoughts were to the African coast. It was the first step of our voyage back to England. We landed at D'Jid Jelli (sic) where we were placed in a camp on the site of an auxiliary landing field. After a few days, much to the joy of everyone, our journey was resumed, to Algiers, thence to Gibraltar and out into the Atlantic.

And so for the last time (or will it be the last time?) we saw the shores of Sicily recede in the distance, but we weren't looking back, our eyes and thoughts were to the African coast. It was the first step of our voyage back to England. We landed at D'Jid Jelli (sic) where we were placed in a camp on the site of an auxiliary landing field. After a few days, much to the joy of everyone, our journey was resumed, to Algiers, thence to Gibraltar and out into the Atlantic.

Combined Operations, pages 100 - 101, written by 'a Canadian LCM Flotilla Engineer Officer'

*the words 'a reporter from the Montreal Star' led me on an earlier, longer and very rewarding research project (33 posts on this site; see Directory A-Z (see right hand margin - go to Editor's Research, then to Editor's Research: Montreal Star), though I was unable to ascertain who The Star reporter was nor find a news article confirming the above story. (Link to my concluding piece at Editor's Research: Invasion of Italy (33) - Montreal Star (Dec. 9-11, '43). But, I think it's out there, perhaps to be found in the Montreal Gazette or Montreal Standard. More research to follow at UWO once COVID-19 allows me access to their vast cache of microfiche! Editor, GH.

*the words 'a reporter from the Montreal Star' led me on an earlier, longer and very rewarding research project (33 posts on this site; see Directory A-Z (see right hand margin - go to Editor's Research, then to Editor's Research: Montreal Star), though I was unable to ascertain who The Star reporter was nor find a news article confirming the above story. (Link to my concluding piece at Editor's Research: Invasion of Italy (33) - Montreal Star (Dec. 9-11, '43). But, I think it's out there, perhaps to be found in the Montreal Gazette or Montreal Standard. More research to follow at UWO once COVID-19 allows me access to their vast cache of microfiche! Editor, GH.

Further along in Combined Operations we read the following 'suitable conclusion' regarding Operation Avalanche (Salerno):

H.M.S. Uganda was hit a few hours later and severely damaged, though both she and the Savannah survived. During the next few days several ships were victims of the formidable new weapon, including the battleship Warspite. She had been shelling the shore batteries. She had just blown up an ammunition dump, and was moving contentedly to the north to shoot up another area, when three remote-controlled bombs came whistling down on her. Two were misses, but the third burst in one of her boiler rooms. In less than an hour her engine rooms were flooded and she was helpless. A hazardous tow of 300 miles brought her to Malta. It took five hours to get her through the Straits of Messina, due to the strong currents.

On shore, the race, as usual was between our own build-up and the arrival of German reinforcements. The critical period began on the evening of the 13th, the fifth day of the fighting. The British were in Salerno town, though the heights above it were in dispute. On the other side of the Gulf the Americans were in Agropoli. The deepest penetration on any part of the front was five miles, and it averaged less than four.

Mark Clark's Headquarters had been established ashore for 36 hours. The Germans had been building up near Eboli, on the edge of the hills north of the Sele River; and that evening with the best part of four divisions and a large number of Tiger tanks, they drove a wedge between the British and the American forces, bursting out on to the plain and getting perilously close to the sea. Their guns were shelling the beaches and their aircraft bombing them. The closer they pressed, the more difficult became our own troop movements in an area which was getting more and more constricted.

Once again, Naval bombardment was called into play, and quantities of shells were fired; while the Allied Air Force made the most concentrated attacks that had ever been made in a battle area in one day.

Once again, Naval bombardment was called into play, and quantities of shells were fired; while the Allied Air Force made the most concentrated attacks that had ever been made in a battle area in one day.

The German War Diary states that the heavy ships' bombardment and the almost complete command of the fighting area by the far superior enemy air force, had cost us grevious losses. By the 16th, the Eighth Army was drawing near from the south, and its leading patrols making contact with the Americans. The German bolt was shot and the Salerno battle saved; but as a measure of how nearly the German counter-strike succeeded, Clark's Headquarters had had to re-embark, and preliminary orders had been issued for the abandonment of some of the southern beaches.

It is pleasant to record that the three Winettes - Boxer, Thruster and Bruiser - played a notable part in this operation. They made six separate trips between the beaches and bases ports in Sicily and Tunisia, and could have made more if they had not, on one voyage, been kept waiting about for 40 hours unloaded. They put 1345 guns and vehicles and 6000 officers and men ashore into the beachhead at a time when they were badly needed. The same applied to many officers and ratings on the LCT's and the LST's who were deeply and severely involved in the landings.

So ended Salerno, a hard and difficult battle, the severest test so far of the technique of Combined Operations.

It is pleasant to record that the three Winettes - Boxer, Thruster and Bruiser - played a notable part in this operation. They made six separate trips between the beaches and bases ports in Sicily and Tunisia, and could have made more if they had not, on one voyage, been kept waiting about for 40 hours unloaded. They put 1345 guns and vehicles and 6000 officers and men ashore into the beachhead at a time when they were badly needed. The same applied to many officers and ratings on the LCT's and the LST's who were deeply and severely involved in the landings.

So ended Salerno, a hard and difficult battle, the severest test so far of the technique of Combined Operations.

Combined Operations, pages 104 - 105

Two other books that contain Navy veterans' stories (RCNVR, Combined Ops) were inspired by the printing and distribution of Combined Operations in 1993 or 1994 and in St. Nazaire to Singapore: The Canadian Amphibious War 1941 - 1945 Vol. 1 (edited by David and Kit Lewis and Len Birkenes) we find a couple of items about the winding down of the Canadian Navy's involvement (as far as Combined Ops is concerned) in Salerno and Operation Avalanche.

In a diary kept by Keith Beecher, LT(E), RCNVR we read the following about the last days of an officer connected to the Canadian 55th Flotilla of Landing Crafts and linked to Avalanche:

Photo Credit - St. Nazaire to Singapore, Volume 1

pg. 153 - 154, University of Alberta (Calgary)

On pages 197 and 198 of the same text as above, one reads of matters of some significance re the work of Canadians in The Med and the eventual winding down of their efforts:

Just before the departure for Northern Sicily in preparation for the jump across the Straits of Messina, it was decided that the 81st Flotilla would not be sent. The 80th Flotilla therefore sailed alone from Malta on August 27 (1943). They picked up a solitary 81st LCM 1 (landing craft, mechanized) and crew who had been left at Syracuse.

Thirty-six hours later they began to embark the Canadians of the Royal 22nd Regiment, the West Nova Scotians, and the Carleton and Yorks.

The Royal 22e Regiment landing on the beach

at Reggio di Calabria on the morning of September 3rd, 1943

Photo - Alexander M. Stirton. Department of National Defence,

National Archives of Canada, PA-177114.

Canadian soldiers and Canadian sailors were operating together at last.

For a month after the lightly opposed Italian landing, the 80th Flotilla carried out its familiar routine of ferry work. The end came with the Italian Armistice and a great celebration in which the population of the countryside joined, and after that the word "England" was on every man's lips.

The 61st Assault Flotilla had long been in the U.K. The 81st was also there.

The 80th arrived on October 27. The 55th Flotilla on board Otranto remained in Algiers and prepared for the landings at Salerno. (See LT (E) Beecher's Diary)*

After a time we were sleeping in casas or houses and I had a helper, a little Sicilian boy named Pietro. First of all I scrubbed him, gave him toothpaste, soap and food. He was cute, about 13 or 14 years of age, but very small because of malnutrition. His mother did my washing and mending for a can of peas or whatever I could scrounge. I was all set up.

When Italy caved in there was a big celebration on the beach, but I had changed my abode and was sleeping with my hammock, covered with mosquito netting, slung between two orange trees. I didn’t join in the celebration because I’d had enough vino, and you not only fought Germans and Italians under its influence, you fought your best friend.

We had some days off and we travelled, did some sight seeing, e.g., visiting German graves. We met Sicilian prisoners walking home disconsolately, stopped them, and took sidearms from any officer. We saw oxen still being used as draft animals when we were there. Sometimes we went to Italy and to Allied Military Government of Occupied Territory depot (AMGOT). (They later changed that name because in Italian it meant shi-!) While a couple of ratings kept the man in charge of all the revolvers busy, we picked out a lot of dandies. If he caught us we were ready. We had chits made out, i.e., “Please supply this rating with sidearms,” signed Captain P.T. Gear or Captain B.M. Lever, after the Breech Mechanism Lever on a large gun.

I learned quite a bit of the Sicilian language under Pietro’s tutelage. He did all my errands and I would have sure liked to have brought him home. It broke my heart to leave him.

After our work from Sicily to Italy was done and our armies were advancing, we returned to Malta. We stayed but a few days, then took MT boats to Bougie in Algiers, and were soon after loaded onto a Dutch ship, the Queen Emma. The ship had been bombed and strafed, her propellor shaft was bent and we could only make eight knots an hour under very rough conditions. Her super structure was easily half inch steel, and in various places where shrapnel had struck I could see holes that looked like a hole punched in butter with a hot poker, like it had just melted.

We arrived at HMCS Niobe barracks in Scotland and in true navy style were put on a train and sent to Lowestoft in England, not too far from Norwich, England (my hometown’s namesake or visa versa) on or near the east coast.

I heard mess deck buzz (rumours). We were getting a lot of money and going on leave. The stipulated time for ratings is twenty-four months overseas and we were closing in. No more raids. Thanks God, for pulling me through.

The mess deck buzz proved to be correct, they gave us all a pile of money (pound notes), and I thought it was too many for me because I made a big allotment to my mother. How they ever kept track of our pay I’ll never know, and to my dying day I will believe they gypped me right up to here.

Away I went on leave (after a visit with Stoker Katana), never bothering to answer a ton of mail. I also received eight hundred cigarettes.

We were due for a do and we did it up brown. (Ed. Wine lovers would paint the town red, but Dad liked British ales, something he passed down to me. Cheers!) You couldn’t possibly lose me in London, England even when I was three sheets to the wind. No way....

....After my leave I went back to Lowestoft, then to Greenock, then was loaded on a ship back to Canada and 52 days leave. Mum waited at Brantford Station for every train for days and I never came. And when I did arrive she wasn’t there. But she sure made a big fuss when she saw me and we cried an ocean full of tears. It was nice to be home again, Mum.

It was coming up to Christmas and quite a few times I thought we would never see another one. I thank God for his protection.

"Dad, Well Done" pages 35 - 37

Many Canadians in Combined Operations returned to Canada and soon took on other volunteer duties related to RCNVR and Combined Ops. A navy base on Vancouver Island had become a Combined Ops training camp in the fall of 1943 (HMCS Givenchy III) and dozens of sailors, including my father, volunteered to serve there, assisting in some ways with combined operations training, handling landing crafts once again.

The 80th arrived on October 27. The 55th Flotilla on board Otranto remained in Algiers and prepared for the landings at Salerno. (See LT (E) Beecher's Diary)*

From pages 198 - 199 St. Nazaire to Singapore, Volume 1 in a section called Sicily and Italy by Lt. Cdr Lloyd Williams

*(Editor: And we have done so).

Before my father arrived back in England in late October he had to wave a tearful good-bye to a young lad who acted as a tour and language guide when the 80th was operating out of Messina.

He writes about leaving Italy in memoirs as well as in a news column for his home town newspaper, The Norwich Gazette.

One night shortly after that event (his 23rd birthday, Sept. 6, 1943) I was all snug in my hammock, mosquito netting all tucked in (it took a while). I was ready to drop off to sleep when all hell broke loose on the beach.

Machine gun fire, tracer bullets drawing colourful arcs in the dark sky. Someone shook my hammock and asked if I was coming to the beach party - Italy had thrown in the sponge.

I said, “No, I’m not coming, and would you please keep it down to a dull roar because I want to log some sleep.”

After about a month Do-go (one of his nicknames; another was 'Cactus') had a tearful goodbye with his friend Peepo (Pietro Guiseppe; his mother did Dad's laundry in exchange for food and compost tea). He stood on the beach and I on my landing craft, waving our goodbyes. What a strange war. I have thought of him often.

Our flotilla went back to Malta for a few days and from there we took fast Motor Torpedo boats to Bougie in North Africa and boarded a Dutch ship, the Queen Emma, whose propellor shaft was bent from a near miss with a bomb. In convoy we made about eight knots up the Mediterranean to Gibraltar, anchored inside the submarine nets for a couple of days, and slowly moved out one night for England.

In true navy fashion, after landing at Gourock, near our Canadian barracks H.M.C.S. Niobe in Greenock (Scotland), we entrained for a barracks at Lowestoffe, where on a clear day the church spires of Norwich could be seen. We spent a month there, then went by train to Niobe, received two new uniforms and a ticket aboard the Aquitania, arriving safely at Halifax on December 6th, 1943.

I had a wonderful Christmas at home with Mother and family. It was sure nice to walk down Main Street (Norwich, Ontario) and meet the people.

One night shortly after that event (his 23rd birthday, Sept. 6, 1943) I was all snug in my hammock, mosquito netting all tucked in (it took a while). I was ready to drop off to sleep when all hell broke loose on the beach.

Machine gun fire, tracer bullets drawing colourful arcs in the dark sky. Someone shook my hammock and asked if I was coming to the beach party - Italy had thrown in the sponge.

I said, “No, I’m not coming, and would you please keep it down to a dull roar because I want to log some sleep.”

After about a month Do-go (one of his nicknames; another was 'Cactus') had a tearful goodbye with his friend Peepo (Pietro Guiseppe; his mother did Dad's laundry in exchange for food and compost tea). He stood on the beach and I on my landing craft, waving our goodbyes. What a strange war. I have thought of him often.

Our flotilla went back to Malta for a few days and from there we took fast Motor Torpedo boats to Bougie in North Africa and boarded a Dutch ship, the Queen Emma, whose propellor shaft was bent from a near miss with a bomb. In convoy we made about eight knots up the Mediterranean to Gibraltar, anchored inside the submarine nets for a couple of days, and slowly moved out one night for England.

In true navy fashion, after landing at Gourock, near our Canadian barracks H.M.C.S. Niobe in Greenock (Scotland), we entrained for a barracks at Lowestoffe, where on a clear day the church spires of Norwich could be seen. We spent a month there, then went by train to Niobe, received two new uniforms and a ticket aboard the Aquitania, arriving safely at Halifax on December 6th, 1943.

I had a wonderful Christmas at home with Mother and family. It was sure nice to walk down Main Street (Norwich, Ontario) and meet the people.

"Dad, Well Done" pages 116 - 117

Aboard the Aquitania which arrived “safely at Halifax on Dec. 6th, 1943”

L - R: Chuck ‘Rosie’ Rose, Don ‘Westy’ Westbrook, foreground, with

Joe Watson straightening his collar and my father, Do-go, behind him

Below is a story that not only mentions the return to England but details about a sailor's payday.

When Italy caved in there was a big celebration on the beach, but I had changed my abode and was sleeping with my hammock, covered with mosquito netting, slung between two orange trees. I didn’t join in the celebration because I’d had enough vino, and you not only fought Germans and Italians under its influence, you fought your best friend.

We had some days off and we travelled, did some sight seeing, e.g., visiting German graves. We met Sicilian prisoners walking home disconsolately, stopped them, and took sidearms from any officer. We saw oxen still being used as draft animals when we were there. Sometimes we went to Italy and to Allied Military Government of Occupied Territory depot (AMGOT). (They later changed that name because in Italian it meant shi-!) While a couple of ratings kept the man in charge of all the revolvers busy, we picked out a lot of dandies. If he caught us we were ready. We had chits made out, i.e., “Please supply this rating with sidearms,” signed Captain P.T. Gear or Captain B.M. Lever, after the Breech Mechanism Lever on a large gun.

I learned quite a bit of the Sicilian language under Pietro’s tutelage. He did all my errands and I would have sure liked to have brought him home. It broke my heart to leave him.

After our work from Sicily to Italy was done and our armies were advancing, we returned to Malta. We stayed but a few days, then took MT boats to Bougie in Algiers, and were soon after loaded onto a Dutch ship, the Queen Emma. The ship had been bombed and strafed, her propellor shaft was bent and we could only make eight knots an hour under very rough conditions. Her super structure was easily half inch steel, and in various places where shrapnel had struck I could see holes that looked like a hole punched in butter with a hot poker, like it had just melted.

We arrived at HMCS Niobe barracks in Scotland and in true navy style were put on a train and sent to Lowestoft in England, not too far from Norwich, England (my hometown’s namesake or visa versa) on or near the east coast.

I heard mess deck buzz (rumours). We were getting a lot of money and going on leave. The stipulated time for ratings is twenty-four months overseas and we were closing in. No more raids. Thanks God, for pulling me through.

The mess deck buzz proved to be correct, they gave us all a pile of money (pound notes), and I thought it was too many for me because I made a big allotment to my mother. How they ever kept track of our pay I’ll never know, and to my dying day I will believe they gypped me right up to here.

Away I went on leave (after a visit with Stoker Katana), never bothering to answer a ton of mail. I also received eight hundred cigarettes.

We were due for a do and we did it up brown. (Ed. Wine lovers would paint the town red, but Dad liked British ales, something he passed down to me. Cheers!) You couldn’t possibly lose me in London, England even when I was three sheets to the wind. No way....

....After my leave I went back to Lowestoft, then to Greenock, then was loaded on a ship back to Canada and 52 days leave. Mum waited at Brantford Station for every train for days and I never came. And when I did arrive she wasn’t there. But she sure made a big fuss when she saw me and we cried an ocean full of tears. It was nice to be home again, Mum.

It was coming up to Christmas and quite a few times I thought we would never see another one. I thank God for his protection.

"Dad, Well Done" pages 35 - 37

Many Canadians in Combined Operations returned to Canada and soon took on other volunteer duties related to RCNVR and Combined Ops. A navy base on Vancouver Island had become a Combined Ops training camp in the fall of 1943 (HMCS Givenchy III) and dozens of sailors, including my father, volunteered to serve there, assisting in some ways with combined operations training, handling landing crafts once again.

About the change of scene my father wrote, "It was heaven."

L - R: Back row - Art Warrick, Hamilton; Ed Chambers; Don Westbrook, Hamilton

Front - Joe Watson, Simcoe; Don Linder, Kitchener, Doug Harrison, Norwich; n/a

Canadians in RCNVR/Comb. Ops on their way to Vancouver Island, January 1944

More details to follow - Editor's Research 11b - related to the U-Boat wars as mentioned earlier in this post.

No comments:

Post a Comment