Early Days in 'the Med'. But Surely the Canadians are Coming!

An Opinion Piece about the Dieppe Raid. (Debate Continues!)

Object description: Bathed in sunlight, part of the invasion armada in line ahead,

leaving Alexandria bound for Sicily. Note the barrage balloons above the ships.

Photo - Allen, E. E. (Lt), Royal Navy official photographer © IWM A 17901

Introduction:

We know that Operation HUSKY - the Allied invasion of Sicily - will soon start, i.e. beginning in the early morning hours of July 10, 1943, 3 and 4 days after the news clippings below hit the bustling streets in Montreal.

And 'if or when' Canadian sailors in the RCNVR and Combined Operations (C. O.) are mentioned in a clip (C. O. was a British organization for which approx. 950 - 1,000 sailors volunteered to handle or man various landing crafts beginning in December, 1941, including my father), you'll be the first to know.

We know that Operation HUSKY - the Allied invasion of Sicily - will soon start, i.e. beginning in the early morning hours of July 10, 1943, 3 and 4 days after the news clippings below hit the bustling streets in Montreal.

And 'if or when' Canadian sailors in the RCNVR and Combined Operations (C. O.) are mentioned in a clip (C. O. was a British organization for which approx. 950 - 1,000 sailors volunteered to handle or man various landing crafts beginning in December, 1941, including my father), you'll be the first to know.

Warning: The news clip does not even need to contain a direct reference to these Canadians. An indirect reference will do, for certain. Even the slightest of references, e.g., something like "a British sailor on a troop ship off the coast of Sicily saw a couple of unidentified sailors fishing from the back of a nearby ship." It could have happened!

Surely he would have shouted, "Blimey, don't you know there's a war on?!?" Really, it could have happened.

You see, my dad (who wrote a lengthy piece about the early hours of the Allied landing near Avola, Sicily) mentioned in passing that while LCAs (landing craft, assault) were landing British troops on the tenth (Monty's Army), he had an hour to himself before LCMs (landing craft, mechanised) were launched from davits on the Pio Pico (a Liberty ship)...... so he went fishing.

Royal Navy and RCNVR sailors kicking tires on an LCM. A 12063

Caption: Landing Craft Types. Inveraray, Scotland, October 1942.

LCM (3), front view with ramp down. Photo Credit - IWM

July 10, 1943. We arrived off Sicily in the middle of the night and stopped about four miles out. Other ships and new LCIs (landing craft infantry), fairly large barges, were landing troops. Soldiers went off each side of the foc’sle, down steps into the water and then ashore, during which time we saw much tracer fire. This was to be our worst invasion yet. Those left aboard had to wait until daylight so we went fishing for an hour or more, but there were no fish.

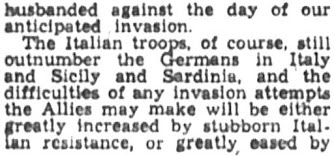

I shared the article below (but not in full) in the previous entry. After reading it more closely I felt some readers might enjoy the entire piece by Hanson Baldwin. So before I share items from July 6 - 7... here's an item from the 5th:

Please click on the link below to view more news items related to July 6, 1943:

Another rare, home-grown Canadian story:

My father writes the following in memoirs:

My group (many from Effingham Division, HMCS Stadacona, Halifax, Canada) went through much more training at H.M.S. Quebec (No. 1 Combined Operations Training Camp, Inveraray, Scotland) and then we entrained for Liverpool. Prominent pub was The Crown in Wallasey. We left Greenock in October, 1942 with our LCMs aboard a ship called Derwentdale, sister ship to Ennerdale. She was an oil tanker and the food was short and the mess decks where we ate were full of eighteen inch oil pipes. The 80th and 81st flotillas, as we are now called, were split between the Derwentdale and Ennerdale in convoy, and little did we know we were bound for North Africa.

I became an A/B Seaman (Able-bodied) on this trip and passed my exams classed very good. The food aboard was porridge and kippers for breakfast, portioned out with a scale. We would plead for just one more kipper from the English Chief Petty Officer, and when he gave it to us we chucked it all over the side because the kippers were unfit to eat.

We had American soldiers aboard and an Italian in our mess who had been a cook before the war. He drew our daily rations and prepared the meal (dinner) and had it cooked in the ship’s galley. He had the ability to make a little food go a long way and saved us from starvation. Supper I can’t remember, but I know the bread was moldy and if the ship’s crew hadn’t handed us out bread we would have been worse off. We used to semaphore with flags to the Ennerdale to see how they were eating; they were eating steak. One of the crew cheered us up and said, “Never mind, boys. There will be more food going back. There won’t be as many of us left after the invasion.” Cheerful fellow. However, we returned aboard another ship to England, the Reina Del Pacifico, a passenger liner, and we nicknamed the Derwentdale the H.M.S. Starvation.

In the convoy close to us was a converted merchant ship which was now an air craft carrier. They had a relatively short deck for taking off, and one day when they were practicing taking off and landing a Swordfish aircraft failed to get up enough speed and rolled off the stern and, along with the pilot, disappeared immediately. No effort was made to search, we just kept on.

One November morning the huge convoy, perhaps 500 ships, entered the Mediterranean Sea through the Strait of Gibraltar. It was a nice sun-shiny day... what a sight to behold.

On November 11, 1942 the Derwentdale dropped anchor off Arzew (sic) in North Africa and different ships were distributed at different intervals along the vast coast. My LCM had the leading officer aboard, another seaman besides me, along with a stoker and Coxswain. At around midnight over the sides went the LCMs, ours with a bulldozer and heavy mesh wire, and about 500 feet from shore we ran aground. When morning came we were still there, as big as life and all alone, while everyone else was working like bees.

There was little or no resistance, only snipers, and I kept behind the bulldozer blade when they opened up at us. We were towed off eventually and landed in another spot, and once the bulldozer was unloaded the shuttle service began. For ‘ship to shore’ service we were loaded with five gallon jerry cans of gasoline. I worked 92 hours straight and I ate nothing except for some grapefruit juice I stole.

More to soon follow from The Med, and from The Montreal Gazette.

Please click here to view Research: Three Months in the Mediterranean, 1943 (2)

Unattributed Photos GH

"Dad, Well Done", page 31

Really, how bad was the food on the Pio Pico anyway?

[More about the early hours of the landings in Sicily can be found here.]

I shared the article below (but not in full) in the previous entry. After reading it more closely I felt some readers might enjoy the entire piece by Hanson Baldwin. So before I share items from July 6 - 7... here's an item from the 5th:

The last full sentence from the lengthy article above (especially, "upon the events of the next two or three months will depend the course and duration of the war") seems to highlight the same time period with which I am concerned in this series of research entries entitled "Three Months in the Mediterranean, 1943."

Many key events will slowly unfold and the Canadians in Combined Operations will be kept very busy:

The last two paragraphs above, from an Allied correspondent's POV, provide a couple of interesting, perhaps apt, descriptions of the role the island of Sicily played in the POV of an Axis war planner.

Firstly, we are informed that Sicily is "a triangular shield for the Axis defence of southern Europe." And the shield will apparently be a tough nut to crack.

Secondly, "the enemy Sicily is valuable - to both Axis and Allied forces - as an unsinkable aircraft carrier" because of its location re the transport of troops and all materials of war. Because of its location Sicily had been on the footpath of many warring nations throughout history. The forces of war were not strangers to the island of Sicily.

The people of Sicily might have to this day an understanding of the effects (and/or side-effects) of war that few others would have.

And now a word from the makers of modern day Rogers Cable TV???

What's that around his neck? Early Rogers Communication Systems?

Photo - Special Collectors Edition, Legion Magazine, Winter 2023

The 'Dieppe Experiment' is recalled by the first (now former) Director of Combined Operations:

. . . . in other words, if I may be so bold (concerning the last paragraph above), the second running of the Dieppe Raid (Operation Jubilee) should have been cancelled just as had been the first running (Operation Rutter) about five weeks earlier.

Hitler's aim was always just a bit off!

Commando raids did not go out of fashion after Dieppe. Quite to the contrary. The history of the Commando is quite extensive and can be linked to Crete and - just a wee bit later - Sicily:

Landing craft massed in Bizerte Harbor for the invasion of Sicily. Third Division

troops march aboard, 6 July 1943. Photo Credit - U.S. Army in WW2, Pg. 109

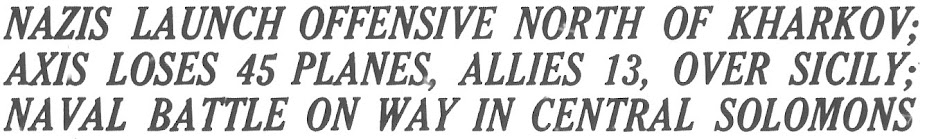

And now we move on to July 7, 1943, also known as "D-Day minus 3" or "D-Day -3":

Regular readers will understand when I say I include news articles that relate to Allied land, sea and air forces but my main focus/interest relates to the Canadians (RCNVR) who played a significant role in Combined Operations. Yes, I am my father's son.

That being said, I have been fortunate to find some special articles that relate to a Canadian airman who not only flew a Spitfire in 'the Med' but made a significant sighting during a recon flight over Italy in September, 1943. More details* momentarily...

* details - FO John Anthony Vasicek (RCAF Spitfire) described a rare sighting, made a significant report (a "first"), but never returned home after his last recon flight. I had the pleasure of meeting his younger brother a few years ago. Link - Editor's Research: FO John Anthony Vasicek RCAF

Photo from the collection of Charles and Bessie Vasicek

Lord Keyes has something to say about "a commando enterprise (that) was cancelled - see paragraph 1 below- on the eve of sailing for Italy...":

Note to self: Look for Keyes' book - Amphibious Warfare and Combined Operations - at my favourite used book store!

FYI - re to the headline atop the above map, i.e., "The Backdoor to Europe." One of the war correspondents for The Montreal Gazette, already featured in earlier posts in this series, wrote a book soon after his tour in 'the Med' was over entitled "They Left the Backdoor Open". More information about the excellent book by Lionel S.B. Shapiro can be found here.

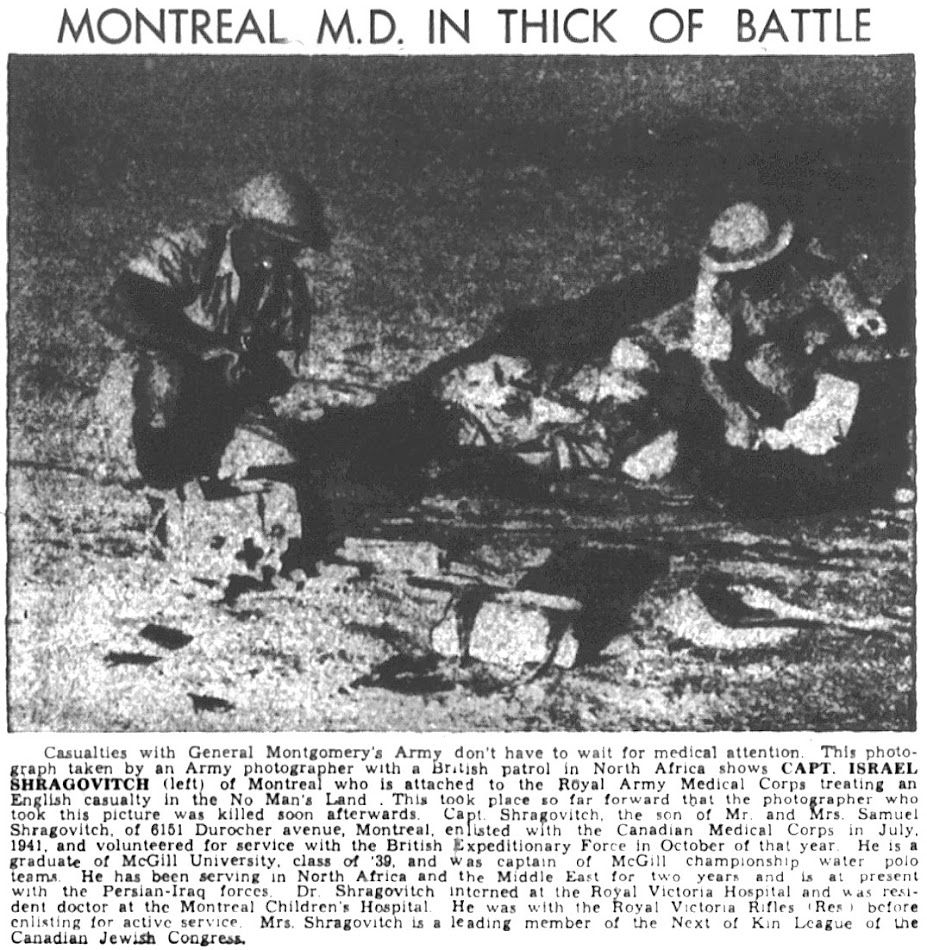

And now more about a Montreal M.D. as found in The Montreal Gazette:

Finally, something about the Canadian Navy! And yes, they are on the way to Sicily as well!

That being said, though the article directs praise toward the R.C.N. contribution re Operation TORCH, the invasion of North Africa, the Canadians (RCNVR) in Combined Ops are not mentioned. I have something to say about that... later:

Editor's Note: I would say that approximately 200 more Canadian sailors should be added to the "cold statistics" mentioned in paragraph one, above. Though the sailors did not man "the diminutive fighting craft" mentioned in paragraphs 4 - 5 (likely referring to corvettes), they manned other small, speedy, essential crafts, e.g., LCAs (landing craft, assault) and LCMs (landing craft, mechanised) while transporting U.K and U.S. troops and all their materials of war to shore at and near Oran and at other beaches in Algeria.

Members of RCNVR and Combined Operations participated in landings

during Operation TORCH (beginning Nov. 8, 1942) east of Oran as part

of the Center Task Force, and farther east at and near Algiers.

Canadian sailors, manning LCAs and LCMs landed U.S. Rangers east of Oran, at Arzeu, as part of the 'Oran Eastern Landing Group' (see the top of the right side on the map below).

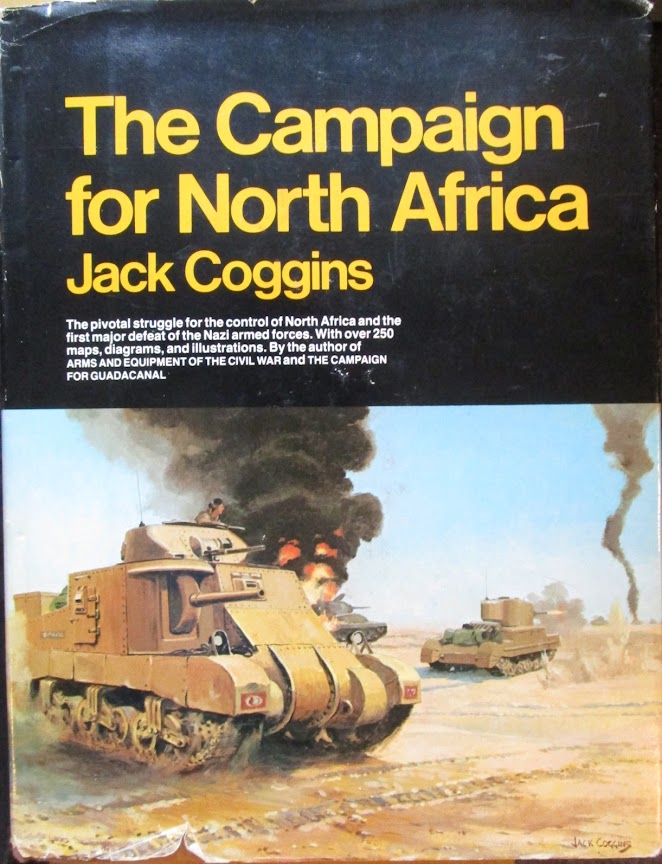

The map above is from the book below:

My group (many from Effingham Division, HMCS Stadacona, Halifax, Canada) went through much more training at H.M.S. Quebec (No. 1 Combined Operations Training Camp, Inveraray, Scotland) and then we entrained for Liverpool. Prominent pub was The Crown in Wallasey. We left Greenock in October, 1942 with our LCMs aboard a ship called Derwentdale, sister ship to Ennerdale. She was an oil tanker and the food was short and the mess decks where we ate were full of eighteen inch oil pipes. The 80th and 81st flotillas, as we are now called, were split between the Derwentdale and Ennerdale in convoy, and little did we know we were bound for North Africa.

later these sailors were in N. Africa, volunteers in Combined Operations

We had American soldiers aboard and an Italian in our mess who had been a cook before the war. He drew our daily rations and prepared the meal (dinner) and had it cooked in the ship’s galley. He had the ability to make a little food go a long way and saved us from starvation. Supper I can’t remember, but I know the bread was moldy and if the ship’s crew hadn’t handed us out bread we would have been worse off. We used to semaphore with flags to the Ennerdale to see how they were eating; they were eating steak. One of the crew cheered us up and said, “Never mind, boys. There will be more food going back. There won’t be as many of us left after the invasion.” Cheerful fellow. However, we returned aboard another ship to England, the Reina Del Pacifico, a passenger liner, and we nicknamed the Derwentdale the H.M.S. Starvation.

In the convoy close to us was a converted merchant ship which was now an air craft carrier. They had a relatively short deck for taking off, and one day when they were practicing taking off and landing a Swordfish aircraft failed to get up enough speed and rolled off the stern and, along with the pilot, disappeared immediately. No effort was made to search, we just kept on.

One November morning the huge convoy, perhaps 500 ships, entered the Mediterranean Sea through the Strait of Gibraltar. It was a nice sun-shiny day... what a sight to behold.

U.S. troops climb into landing craft, manned by Canadians, from Reina Del

Pacifico during landings in North Africa, Nov. 1942. Photo credit - IWM

On November 11, 1942 the Derwentdale dropped anchor off Arzew (sic) in North Africa and different ships were distributed at different intervals along the vast coast. My LCM had the leading officer aboard, another seaman besides me, along with a stoker and Coxswain. At around midnight over the sides went the LCMs, ours with a bulldozer and heavy mesh wire, and about 500 feet from shore we ran aground. When morning came we were still there, as big as life and all alone, while everyone else was working like bees.

There was little or no resistance, only snipers, and I kept behind the bulldozer blade when they opened up at us. We were towed off eventually and landed in another spot, and once the bulldozer was unloaded the shuttle service began. For ‘ship to shore’ service we were loaded with five gallon jerry cans of gasoline. I worked 92 hours straight and I ate nothing except for some grapefruit juice I stole.

“DAD, WELL DONE” Naval Memoirs of G. D. Harrison, pages 23 - 25

Doug Harrison (centre) watches as troops and ammunition come ashore on LCAs

at Arzeu in Algeria during Operation TORCH, Nov., 1942. Photo credit - IWM

American troops landing on the beach at Arzeu, near Oran, from a landing

craft assault (LCA 26), some of them are carrying boxes of supplies.

Photo Credit - Imperial War Museum (IWM)

Editor's Final Note: The last news article shared above described the role of Canada's Navy in the following way:

I do not disagree with its description as a "flyweight" or the work often being the "tedious, thankless, escorting task of the convoy." I would just add a bit to 'Her role.' Canada's Navy was not only "protecting the supply line which nourished the British divisions," it was an active, significant (and often over-looked) link in the actual supply line, one that delivered U.S. and U.K troops and all their materials of war to many beachheads, sometimes fuelled by no more than stolen grapefruit juice.

And that their role was oft over-looked is likely related to this numerical fact. Only about 950 - 1,000 members of RCNVR (officers and ratings) volunteered for Combined Operations, out of all those who volunteered (95,000 - 100,000) for the RCN and RCNVR during WWII. 1 per cent of the Navy is a pretty thin slice of the overall role of Canada's Navy.

That being said, since the 1% had front row seats in several raids (including St. Nazaire and Dieppe) and Allied invasions (including Operations TORCH (N. Africa), HUSKY (Sicily), BAYTOWN and AVALANCHE (Italy), NEPTUNE (Normandy, France), and more), their collected stories are an invaluable piece of World War II history.

(Questions or comments can be addressed to me at gordh7700@gmail.com)

And now back to The Gazette:

Please click here to view Research: Three Months in the Mediterranean, 1943 (2)

Unattributed Photos GH

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment